How to Overcome Inner Resistance | Steven Pressfield

Listen or watch on your favorite platforms

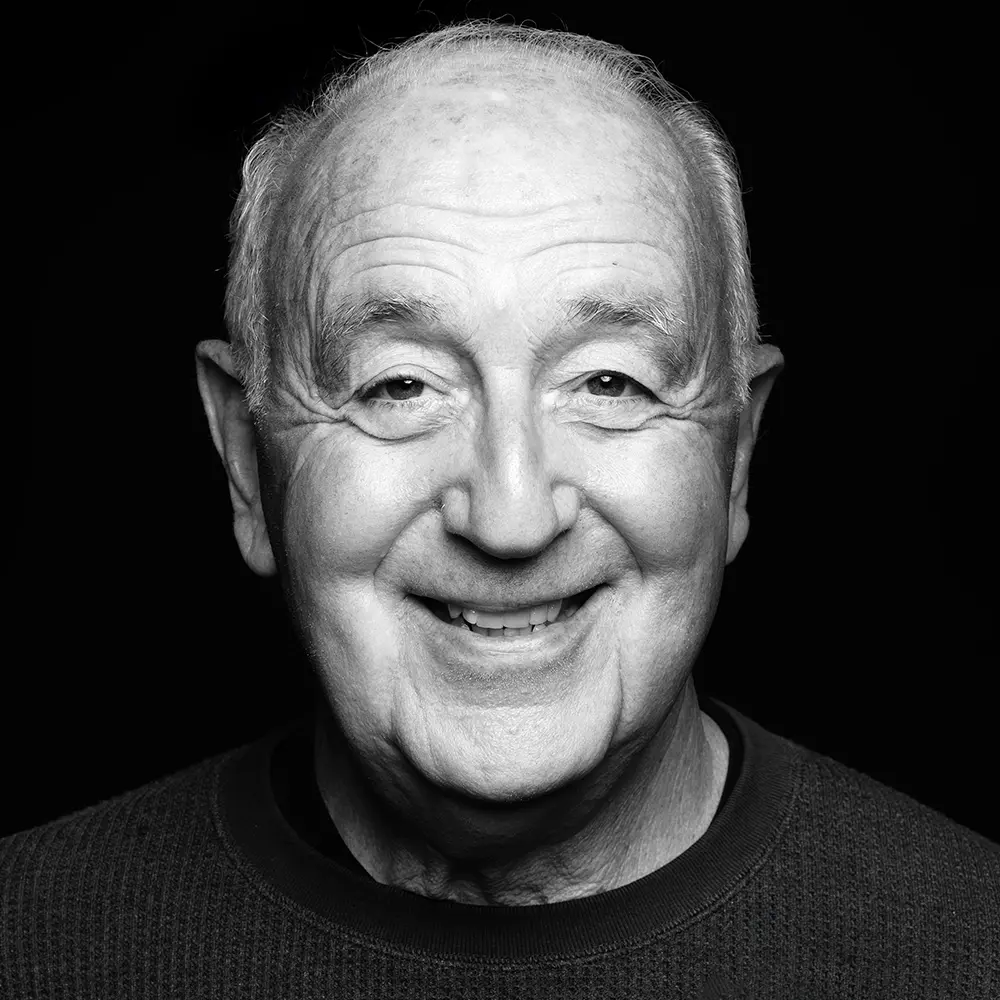

My guest is Steven Pressfield, author of The War of Art and expert in how to overcome the inner force of "resistance"—the self-sabotaging tendency to procrastinate on your life's most important work that keeps you from realizing your professional and creative potential. Steven shares actionable tools for defeating inner resistance that work. His approach is concrete, not based on slogans or inspirational messages. As the author of numerous best-selling books and screenplays, Steven's routines for cultivating discipline and focus, including his physical training regimen (he is incredibly mentally and physically vigorous at 82), are applicable by anyone. He gives you effective practical strategies for how to structure your day, overcome procrastination and self-doubt and do your best, most meaningful work.

Books

- The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles

- Do the Work: Overcome Resistance and Get Out of Your Own Way

- Turning Pro: Tap Your Inner Power and Create Your Life's Work

- Gates of Fire: An Epic Novel of the Battle of Thermopylae

- Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t: Why That Is And What You Can Do About It

- Govt Cheese a memoir

- The Arcadian: A Novel

- A Man at Arms: A Novel

- Steve Jobs

- Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman's Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia

- The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

- Chocolate Days, Popsicle Weeks

- The Odyssey of Homer: Translated by T.E. Lawrence

Movies Mentioned

- The Fighter

- Silver Linings Playbook

- Joy

- The Dark Knight

- King Kong Lives

- Alien

- That Thing You Do!

- The Godfather Part II

- My Big Break

- Good Will Hunting

Other Resources

Huberman Lab Episodes Mentioned

- Dr. Bernardo Huberman: How to Use Curiosity & Focus to Create a Joyful & Meaningful Life

- What Alcohol Does to Your Body, Brain & Health

- How to Make Yourself Unbreakable | DJ Shipley

- Science & Health Benefits of Belief in God & Religion | Dr. David DeSteno

People Mentioned

- Randall Wallace: screenwriter, film director

- Steven Spielberg: film director, producer, screenwriter

- Ernest Hemingway: novelist, short story writer, Nobel laureate

- Robert Redford: actor, director

- Mike Mentzer: bodybuilder, trainer

- Jack Johnson: singer, songwriter

- Jack Carr: author

- Micky Ward: boxer

- T.R. Goodman: fitness trainer

- David O. Russell: director, screenwriter

- Jack Epps Jr: writer, producer

- Seth Godin: author

- Sean Coyne: editor, book publisher

- Edmund Hillary: mountaineer, explorer

About this Guest

Steven Pressfield

Steven Pressfield is a bestselling author and screenwriter known for his influential works on creativity and resistance, including The War of Art, as well as historical novels like Gates of Fire and his screenplay for The Legend of Bagger Vance.

This transcript is currently under human review and may contain errors. The fully reviewed version will be posted as soon as it is available.

Steven Pressfield: For years, when I was struggling and could never get it together, I realized that at one point that I was just thinking like an amateur. And that if I could flip a switch in my mind and think like a professional, that I could overcome some of the things. A professional shows up every day. A professional stays on the job all day, or with the equivalent of all day. A professional, as I said this before, does not take success or failure personally.

Steven Pressfield: An amateur will, right? An amateur gets a bad review or bad response of this, and they just crap out, "I don't want to do this anymore." A professional plays hurt. Like if Kobe Bryant or Michael Jordan, if they've tweaked a hamstring, they're out there, you know? They'll die before they'll be taken off the court. Whereas an amateur, when he or she confronts adversity, will fold.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: "Oh, it's too cold out, you know, I've got the flu." Da-da, that kind of thing. An amateur worries about how they feel. Like, "Oh, I don't feel like getting out of bed this morning. I don't feel like really doing my work today." A professional doesn't care how they feel, they do it. So an amateur has amateur habits, and a professional has professional habits.

Andrew Huberman: Welcome to the Huberman Lab podcast, where we discuss science and science-based tools for everyday life. I'm Andrew Huberman, and I'm a professor of neurobiology and ophthalmology at Stanford School of Medicine. My guest today is Steven Pressfield.

Andrew Huberman: Steven Pressfield is an author of numerous historical fiction and non-fiction books, including the now iconic "War of Art" and also the book "Do the Work," which both focus on understanding the forces in our minds that barrier us from being our most focused, creative, and productive selves, and more importantly, how to overcome those barriers.

Andrew Huberman: Perhaps it's because Steven worked hard physical labor jobs and was in the military prior to becoming a book author and screenwriter. Or perhaps it's because he published his first book at age 52 that Steven really understands how to persevere and overcome inner doubt and procrastination, and turn creative blocks into important creative works. As you'll hear during today's episode, Steven doesn't talk in inspirational slogans or metaphors.

Andrew Huberman: So none of this "get after it," or you know, "You just have to do the work." Instead, he gets very concrete about how to structure your day, how to frame your goals and your setbacks, and even how to make your creative environment more conducive to focus and effort. We also talk about how to capture your best ideas, which, by the way, often occur away from the work that you're actually trying to do, and how to implement them.

Andrew Huberman: So, if you have an idea or you're searching for an idea for a creative project to share with the world, this conversation will be immensely useful to you. It will also be extremely useful to anyone who suffers from procrastination and self-doubt, which, frankly, I think is all of us at some point or another.

Andrew Huberman: I read Steven's book, "The War of Art", some years ago, and I loved it. It transformed the way that I did my science, how I approached the podcast, and many, many other aspects of life. You'll also notice that at 82 years old, Steven is incredibly sharp and fit. So we talk about his physical regimen and the important role that it plays in keeping his mind active, productive, and overcoming resistance.

Andrew Huberman: Steven is not only very accomplished, he's also truly wise and generous. And today, he shares a wealth of practical wisdom with us. Before we begin, I'd like to emphasize that this podcast is separate from my teaching and research roles at Stanford. It is, however, part of my desire and effort to bring zero-cost to consumer information about science and science-related tools to the general public. In keeping with that theme, today's episode does include sponsors. And now for my discussion with Steven Pressfield.

Andrew Huberman: Steven Pressfield, welcome.

Steven Pressfield: Andrew, it's a pleasure to be here. We're former neighbors, you know, so we've been talking about this for a while. It's great to be here.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, I've been wanting to do this for a while. I've been reading your books for, goodness, a couple of decades now or more.

Andrew Huberman: "First War of Art," and then I started through the library, you've written a lot of books, nonfiction and fiction. It's been super impactful to me and many other people. I think everybody deals with procrastination. You'll tell us about resistance. But there's a quote out there that they claim is you. I'm going to assume it's you. And I recommend accepting that it's you, even if it's not, because it's a beautiful quote.

Steven Pressfield: I'm laughing already.

Steven Pressfield: If it's a good quote, I'll take credit for it.

Andrew Huberman: It's great. And I'd like your reflections on it and what you intended when you said it, which is, "The more important to your soul's growth, the stronger the resistance will be." Which, for me, was very counterintuitive.

Steven Pressfield: Uh.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: Because we all imagine the creative process as one of being inspired, "Ah, this is my soul's work," and having a ton of motivation to get the work done, a ton of desire and drive. But the more important to your soul's growth, the stronger your resistance will be. Interesting.

Steven Pressfield: Well, that's absolutely true. And what I meant by that was that when we conceive an idea for something we want to do, a movie we want to make, or a book we want to make, it's not at all like what the fantasy was, "Oh, I'm really charged up, it's going to be great." What happens is waves of what I call Resistance with a capital R start coming off that keyboard or whatever it is to try to stop us from doing it.

Steven Pressfield: Make us procrastinate, make us go to the beach, make us just give in to distractions, so on and so forth. But the weird principle is, and this is why I always say, if you want to know which one of three or four projects that you should do, you should do the one you're most afraid of.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Because that fear is a form of Resistance with a capital R.

Steven Pressfield: And the more important a project is to your soul's evolution, not to your commercial success, but to your own evolution as an artist, the more resistance you will feel to it. So, in other words, the thing that you really should be doing is going to be the hardest, and it's going to punch you in the face the hardest. Which is why so many artists have such a hardcore professional attitude, because they have to have it to be able to kind of stand up to that resistance. They're trying to push them away from doing their project, whatever it is.

Andrew Huberman: The more important to your soul's evolution, the more resistance you're going to experience, but that's the project you should be doing.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. Here's an analogy that I use sometimes, Andrew, and you may have heard me say this before. I think about... If you can imagine a tree in the middle of a sunny meadow. As soon as the tree appears, a shadow is going to appear, and the shadow is going to be-- The tree is your dream, whatever it is, right? A book, a movie, whatever. And the shadow is the resistance you're going to feel, and they're directly proportionate to each other.

Steven Pressfield: The bigger the tree, the bigger the shadow. So, when you feel that shadow, you feel that massive resistance, "Oh, I want to quit. I don't want to-- I'm not good enough to do this," et cetera, et cetera, that's a good sign, in that it says that the tree, your dream, is really big, and so you have to do it. You don't want to take a little tree. You want to take the big tree.

Andrew Huberman: You have military training and background. You were a Marine, correct?

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. I was a reservist Marine, infantryman.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: How much does your training as a Marine impact this concept of resistance and your suggestions for people and your ability to push through resistance?

Steven Pressfield: A tremendous amount.

Steven Pressfield: You know, I think when I was going through boot camp and infantry training and stuff like that, I hated it, and I thought, "I just can't wait until I get out of this and just be a regular civilian again." But as I've grown and lived through the artist life of writing, being in a room with your own demons for two or three years at a time.

Steven Pressfield: I've learned that kind of the virtues that you learn in the military are the same virtues that you have to call upon to live that war of art, the war inside your head. You know, the virtues of stubbornness, of the willing embracing of adversity, of patience, of selflessness, and of courage, because it's about fear.

Steven Pressfield: And so yeah, it's influenced me tremendously, and I found, sort of to my amazement, as I started writing fiction, that I was drawn to themes of war, even though I've never actually been in a war. But it's the inner war that interests me, the metaphor of war. So yeah, a lot. It meant a lot.

Andrew Huberman: Do you think the physical training that you took part in when you were in the Marines has impacted, A, your current physical regimen? By the way, everybody, Steven is 82 years old. I see him at the gym. He's there every morning very early. What time do you get there?

Steven Pressfield: I get there at quarter to 5:00.

Andrew Huberman: Quarter to 5:00 AM, which is why I see him from time to time, because I'm not there at quarter to 5:00.

Steven Pressfield: You're coming in. I'm going home.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, and I sometimes train there and elsewhere, but you are very consistent. You train very early. So clearly, you're in great physical and mental shape. It's awesome to see. With all the discussion about longevity, you are living proof. So what? I am curious about your physical regimen and the extent to which your physical regimen impacts your ability to lean into and against resistance to do your creative work at the keyboard or with pen and paper.

Steven Pressfield: Aah, that's a great question. Going to the gym early, first thing for me, is a rehearsal for when I get home, and I go sit at the keyboard, and I actually have to face the resistance of working that day, right? So, to me, the gym is about something that I don't want to do. I hate to get up that early in the morning and get there. It's something that is going to hurt, right? We all know about that.

Steven Pressfield: And it's something that I'm afraid of, because as you know, there are all kinds of ways you can hurt yourself and embarrass yourself and so on and so forth. But having done that in the morning, so it's for-- I've got like... I think we have a mutual friend in Randy Wallace, right? Do we have-

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. Randy has this thing, Randall Wallace, who wrote "Braveheart" and, as secretary, directed that and many others.

Steven Pressfield: He has a thing in the morning that he calls little successes, and what he's trying to do to build momentum for when he's actually going to sit down and write is achieve something that he can say, "Okay, I did something good here." You know, so going to the gym for me is that. It's not so much about the physical aspect of it.

Steven Pressfield: It's the rehearsal for kind of facing like it's-- So, I feel like when I finish at the gym, nothing I'm going to do for the rest of the day is going to be as hard as what I already did. So, you know, there we go. The ways are greased, and I can go forward. That's the theory, anyway.

Andrew Huberman: So when you wake up in the morning, you're not looking forward to working out?

Steven Pressfield: F***, no. I mean, can we say that here on in?

Andrew Huberman: Sure. Yeah. Absolutely.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Absolutely not. It's a drag. I hate to go, you know?

Andrew Huberman: You prefer to stay in bed?

Steven Pressfield: Absolutely, and I wish I could stay in bed, you know? But on the days I do stay in bed, Sunday, I don't feel so good about myself, you know? I wish I had gone to the gym.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: I mean, you must feel the same way, Andrew, about whatever you do, being an old skateboarder and a fitness guy your whole life. How does it fit in with your regimen?

Andrew Huberman: Well, the problem for me is that I love working out.

Steven Pressfield: Oh, you do?

Andrew Huberman: So, I do, and I always have.

Steven Pressfield: Wow.

Andrew Huberman: I have noticed in the last maybe two or three years that occasionally I have to push myself a little bit more. I loathe rest days, but they are important.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh

Andrew Huberman: You know, I do believe in taking one full day off per week, letting my body recover.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh

Andrew Huberman: But that's the problem, is that I really enjoy working out. And so, by the time I'm done working out and then I shower up, and I eat, and I'm sitting down to do some work, I'm like, "Oh, now comes the really hard workout."

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: But I noticed that I learn things during those workouts, provided that I don't have my phone with me.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: I might listen to music on my phone, sometimes a podcast or an audiobook, but I do my very best not to be on social media or text during those workouts.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: Because during those workouts, something always comes to mind that I find useful for elsewhere in life, and it usually pops up during a rest period between sets.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: You know, I think exercise takes our brain and body into these unfamiliar states.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: And I think that our unconscious mind geysers stuff up.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: And I think it was the great Joe Strummer of "The Clash" that said, "When you have a thought that feels important, write it down, because you think it will be there later, but certain thoughts and ideas are offered up, and they don't last, at least not in that form. You need to catch them." And so I have a mode of catch, usually in notes.

Steven Pressfield: Mm.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: Do you have a capture method for ideas, whether or not you get them during workouts or in the middle of the night?

Steven Pressfield: I don't have during workouts.

Andrew Huberman: Okay.

Steven Pressfield: I don't seem to get ideas during workouts, but I completely agree with that, you know. They're those ideas, when they come, like in the shower, or when you're on the subway, or when you're driving along the freeway, your mind is occupied in something else, right? Your ego is involved, and somehow it opens the pipeline, and things burble up, and you always think, "Oh, I'll remember that," but you forget.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: It's like a dream, you know?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: They just go away. So yeah, I mean, I'll just dictate it into my phone. I mean, my phone now is full of stuff that I've got to transcribe, but I couldn't agree more with that.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, there's something about the way that our unconscious mind, I feel like it kind of tosses things up for the conscious mind to catch, and in those moments, just like in a dream, we think, "Oh, I'll remember this later."

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: And we don't.

Steven Pressfield: It's amazing how they go away, you know?

Andrew Huberman: They just evanescent.

Steven Pressfield: They're evanescent, you know?

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: It's a beautiful word, and it captures it perfectly.

Steven Pressfield: See, I'm a different believer. I don't believe it's really coming from the subconscious.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: I'm a believer in the goddess. I'm a believer in the muse. I think it's coming from someplace else, you know? And that they're playing with us a little bit, you know? Like, I know Steven Spielberg says, "When an idea comes," he says, "It whispers rather than shouting," which is his way, I think, of saying, you know, it's a very subtle thing that goes away very fast, you know? And you have got to grab it while it's there.

Andrew Huberman: I'd like to take a quick break and acknowledge our sponsor, Helix Sleep. Helix Sleep makes mattresses and pillows that are customized to your unique sleep needs. Now, I've spoken many times before on the Huberman Lab podcast and elsewhere about the fact that getting a great night's sleep is the foundation of mental health, physical health, and performance.

Andrew Huberman: Now, the mattress you sleep on makes a huge difference in terms of the quality of sleep that you get each night. How soft it is, how firm it is, how breathable it is, the temperature all play into your comfort and needs to be tailored to your unique sleep needs.

Andrew Huberman: If you go to the Helix website, you'll take a brief two-minute quiz, and it will ask you questions such as, "Do you tend to sleep on your back, your side, or your stomach?" Maybe you don't know, but it will also ask you, "Do you tend to run hot or cold during the night or the early part of the night?" et cetera.

Andrew Huberman: Things of that sort. Maybe you know the answers to those questions, maybe you don't, but either way, Helix will match you to the ideal mattress for you. For me, that turned out to be the Dusk mattress, D-U-S-K. I started sleeping on the Dusk mattress about three and a half years ago, and it's been far and away the best sleep that I've ever had.

Andrew Huberman: It's absolutely clear to me that having a mattress that's right for you, does improve one's sleep. If you'd like to try Helix, you can go to helixsleep.com/huberman, take that two-minute sleep quiz, and Helix will match you to a mattress that is customized for your unique sleep needs. Right now, Helix is giving up to 20% off all mattress orders. Again, that's helixsleep.com/huberman to get up to 20% off. Today's episode is also brought to us by BetterHelp.

Andrew Huberman: BetterHelp offers professional therapy with a licensed therapist carried out entirely online. I've been doing weekly therapy for well over 30 years, and I've found it to be an extremely important component to my overall health. There are essentially three things that great therapy provides. First of all, it provides a good rapport with somebody that you can trust and discuss issues with. Second of all, great therapy provides support in the form of emotional support or directed guidance with practical issues in your life.

Andrew Huberman: And third, expert therapy can provide useful insights, insights that can allow you to make changes to improve your life, not just your emotional life and your relationship life, but also your professional life. With BetterHelp, they make it very easy to find an expert therapist who can help provide the benefits that come through effective therapy, and it's carried out entirely online, so it's extremely convenient. No driving to the therapist's office, no looking for parking, et cetera.

Andrew Huberman: If you would like to try BetterHelp, go to betterhelp.com/huberman to get 10% off your first month. Again, that's betterhelp.com/huberman.

Andrew Huberman: Tell me more about this, from the goddess, or the gods, or the muse, you know, from outside us, or from God.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Well, you know, if you go back to the ancient Greeks, right? "The Iliad," or "The Odyssey," or any of those other great works always start with an invocation of the muse, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Homer writes, "Goddess, tell this story," you know? And basically, the artist is stepping or taken his ego out of the picture and saying, "I'm not the one that's going to tell you this story about ancient Troy.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: "The goddess will tell through me," so they're sort of asking, "Help me, show me," you know, that kind of thing. And I had a mentor. Rob, we were talking about that earlier, a guy named Paul Rink. He's like, can I get into the weeds on this thing, Andrew?

Andrew Huberman: Please.

Andrew Huberman: Please.

Steven Pressfield: And he sort of introduced me to this concept. This was like the first time I tried to write a book. I was like 27 or something like that. Well, I had actually tried and failed before, but it was the first time I ever finished one, and I used to have breakfast every morning. This was in Carmel Valley, not so far from where you grew up, and with my friend, Paul Rink, who's maybe 30 years older than me. He was an established writer. He knew John Steinbeck and knew Henry Miller from Big Sur. And he told me about the muses, the Greek goddesses, the nine sisters, whose job it was to inspire artists, right?

Steven Pressfield: The classic image of the muse is Beethoven at the piano, and a kind of a shadowy female figure is kind of whispering in his ear, you know, bringing him da-da-da-dum, right? And so he wrote out for me, my friend Paul, the invocation of the muse from-- He typed it out on his Remington manual typewriter, the invocation of the muse from the Odyssey, from Homer's "Odyssey," translation by T.E. Lawrence. And I've kept that.

Steven Pressfield: It burned up in the fire, lost it in the fire, but I've kept that for, like, 50 years, and every morning, before I sit down to work, I say that prayer, you know, out loud and in full earnest. You know, "Goddess, help me." And I'm absolutely a believer in that, that ideas come from another place, and it's our job... And I don't think it's the subconscious. It's our job to open the pipeline and get out of the way.

Andrew Huberman: I love it. I'm totally open to the idea that it's not the unconscious mind or the subconscious, whatever people want to call it. I'm sad to hear that this write-up of invocation of the muse burned. We should probably just mention that we used to be neighbors.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Your home burned in the fires, sadly. The home that I lived in, it was not my home, I was renting it, also burned in the fires. So, my guess is that at some point during today's conversation, we'll talk about loss of objects and items.

Steven Pressfield: Uh huh, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: But it sounds like this one was pretty precious.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. It was a sad thing to lose that, you know?

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: But, you know, it's in my head, you know, so.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: How long is it?

Steven Pressfield: It was on one page.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Double-spaced.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: I would say... To recite, it takes maybe 90 seconds.

Andrew Huberman: Do you have any interest or desire in calling it up now, or a portion of it?

Steven Pressfield: I'll call up just the opening of it, because the middle part is Homer sort of describing the whole story of the "Odyssey."

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: But it starts like this. It goes, "Oh, divine poesy, goddess daughter of Zeus, sustain for me this song of the various-minded man," meaning "Odysseus," and then he kind of goes on to talk about da-da-da-da. And at the end it says, "Make this tale live for us in all its many bearings, oh muse," which I think is a great-- You know, make it live, make it come alive in all its many bearings. And so, you know, that's-- Thanks to my friend Paul, that's been a thing that's been with me for 40 years.

Andrew Huberman: I love it. Well, we'll provide a link to the full script.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: It's in "The War of Art," actually. I wrote this out in "The War of Art."

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: I think it's on page 114 or 115.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah. And if anyone hasn't read "War of Art," it's an absolute must-read. I've read it many times. I have an audiobook form, a hard copy form. It is awesome. It is just awesome. So, when you sit down to write, after you've recited this, how many times in the first 10 minutes do you think your mind flits to something else?

Andrew Huberman: I mean, you're now a pro. Like, you've written many books, and you know what is noise and you know what is signal, and you know if you really need to go to the bathroom or if you don't. You know, well, these are the things that pop up, right?

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Absolutely. Yeah, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: As you point out, resistance comes in. Oh, you know, I need another glass of water.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. Yeah. Right. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Or I'm not caffeinated enough, or there's not enough sunlight coming through my window. Whatever, right?

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: How many times in the first 10 minutes, on a typical day, just give us an average, do you think your mind flits to-- Yeah, like, I wonder what's going on in the news?

Steven Pressfield: That's a great question.

Andrew Huberman: You know, like what's going on in the world? I mean, how many times? One?

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Never.

Andrew Huberman: Two? Never?

Steven Pressfield: Never. Now, that's not to say when I first started, many, many moons ago, that I didn't have a lot of that sort of stuff. But I have... I don't know whether it's just over the years, I'm absolutely a believer in, like, diving straight into the pool, you know? I don't sit there for one second wondering what I'm going to do. I just plunge right in, and, thank goodness, somehow I've learned how to do it, and I just focus full tilt on it. So yeah, I don't have those thoughts at all.

Andrew Huberman: How long do you write in that first bout?

Andrew Huberman: Before you make-

Steven Pressfield: Maybe an hour.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: And then I'll take a little bit of a break.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: I love to do laundry. That's my big thing. I'll put in the laundry at the start, and the load will be done, then I can put it into the dryer. I take a little break, and then I come back and start again for another hour.

Andrew Huberman: Do you enjoy it or you enjoy clean laundry, or both? I mean, we-

Steven Pressfield: I just... I enjoy the, sort of the ritual of it and the craziness of it, you know?

Andrew Huberman: Not me. Not one bit.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: The only thing I enjoy about doing laundry is clearing the lint trap. There's something very satisfying about that.

Steven Pressfield: That's the part I hate. I don't want to do that at all, but...

Andrew Huberman: Interesting. All right. Well, we're not considering, but we'd make good roommates.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Interesting. So for an hour, you're locked in and you're just typing away. How often does your inner critic pop up nowadays versus at the beginning? Meaning the "I don't know if this is going in the right direction." I've heard before that you're just supposed to create and then edit later. What's your process there?

Steven Pressfield: It almost never comes up, the inner critic. Again, it used to. You know, it used to all the time. It was a terrible struggle I had for years.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: You know, you sit down and you think, "Well, does Hemingway... Would Hemingway write this sentence?" You know, right? Or, you know, "What will 'The New York Times' think when I write..." you know? But eventually, over time, you learn that you just can't deal with that bullshit, you know?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: It drives you insane.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: You know, so no, I don't let that inner critic come in, you know? And I'm definitely a believer. At the end of the day, I never read what I wrote.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: And I never look back on it the next day. I believe in multiple drafts. Somebody taught me this one time that think in multiple drafts. This was Jack Epps, the original writer of "Top Gun." I was working for him on a movie project, and he said, "Always think in multiple drafts." And you can only fix so much in one draft. You can only fix one thing in one draft.

Steven Pressfield: So, I usually will think of... And I start a book, maybe 13, 14, or 15 drafts. The last 7 or 8 would be really small, really slight changes.

Steven Pressfield: But I won't look back on the day's work because I'll figure on my next draft, then I'll read it fresh, and it'll look a million times, have a much more clear sense, "Is this any good?" Because if you do it when it's too fresh, you start to drive yourself crazy, you start to... You know, perfectionism, another form of resistance, comes in. So yeah, that's my process. I know a lot of other people don't do it that way, but that's the way I do it.

Steven Pressfield: When the day is done, the bell rings, the office is closed, that's it. I turn off my mind and just let the muse take care of it overnight, and I don't try not to worry about it at all. All I ask myself... I know I'm getting into the weeds here, really, Andrew.

Andrew Huberman: This is... No, it's very important that you get into the weeds because I think you've offered many times through books and other podcasts, the contour and a lot of depth, but I think the more detail, the better. Because everyone will do it slightly differently.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: But I think it's very important. We rarely hear what people's real process is.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: So please, don't edit yourself here.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: At the end of a day's session, all I ask myself is, "Did I put in the time, and did I work as hard as I can?" Quality will take care of itself later, in the next draft or the next draft after that. But I never judge it, you know? And it took a long time to get to that place, to learn that, you know? Because I would drive myself insane for years and years, judging along the way.

Andrew Huberman: How long is the total writing session, depending on how much laundry you have to do?

Steven Pressfield: Great questions. I used to be able to write for four hours.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Now, I can only write for about two. What I tell myself, and I think it's true, is I can do in two hours now what I used to do in four.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: But I stop when I start making mistakes, when I start having typos and things like that. Then it's kind of like a workout at the gym. You know when you've reached the end, "I'm just going to hurt myself if I do another set," you know? The point of diminishing returns. So, when I get tired, I stop, and I don't question it at all.

Steven Pressfield: I don't make myself feel bad about, "Oh, you can get another 10 minutes." Like Steinbeck used to say, pressing forward at the end of a long day to get just a little bit more is the falsest kind of economy, because you pay for it the next day. And Hemingway used to say he always stopped when he knew what was coming next in the story, which I also believe in that too, because that'll help you in that hairy first moment when you're sitting down, because at least you know, "Oh, okay, this is what's going to happen."

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Ah. So, you leave sort of an ellipse in your mind so the next morning you know exactly where to pick up and the entry point is a little easier.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, exactly. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. The analogy to working out is a great one. Years ago, when I started resistance training, I learned from Mike Mentzer. I don't know if you ever overlapped with Mike at Gold's.

Steven Pressfield: No.

Andrew Huberman: He died some years ago.

Steven Pressfield: But just to interrupt for a second, they call it resistance training, which is exactly what we're talking about for art. Yeah. So, but please continue.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Oh, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah?

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, excellent point. No, please. You know, there are a lot of theories out there about resistance training and how best to get muscles to grow and to get stronger, et cetera. At one extreme is you warm up, and then you do one set to absolute failure, maybe a second set you push through. That's kind of the Mentzer high-intensity thing. At the other extreme is volume, just lots and lots and lots of sets.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: And there's been debate about this endlessly, and it has to do with all sorts of factors.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: But the literature is now coming to a place where it's pretty clear that after warming up, the first one or two sets that you do are really the most valuable of a given exercise.

Steven Pressfield: Oh, I didn't know that.

Andrew Huberman: And almost certainly you need more than one set overall. You certainly do. But it's really the intensity that you bring. But here's the point that is strongly analogous to what you're talking about when you say you used to be able to write for four hours a day. Now, you do two, and you tell yourself that you accomplished the same amount in those two. That's almost certainly true based on what we understand about neuroscience and, believe it or not, resistance training in the gym.

Steven Pressfield: Oh, I'm glad to hear that. Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Huh.

Andrew Huberman: And the argument is that as you resistance train, or write, or play volleyball, or do any activity, you develop a better ability to recruit your nervous system to do the necessary work.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: You said you didn't used to be able to just sit down and focus for an hour with minimal interruption in your mind. Now, you can. You learned that. The more intensity that we can bring to something, the more focus we can bring to something, the more taxing it is.

Steven Pressfield: Hmm. Hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Like, if I do one set in the gym with total concentration to absolute failure, which is very difficult to do when you first start training, because you barely know how to do the movement, right?

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: You're still learning. Your nervous system is still learning. You can't inflict the same stimulus with one set that you can later, after you've practiced.

Steven Pressfield: Hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Ah. Makes a lot of sense.

Andrew Huberman: And so, there's this counterintuitive thing that people in the high-performance field are really starting to adopt, and I talk to people in a bunch of different high-performance fields, not just exercise and creative works, that the better you get at something, the shorter your real work bouts should be and the more intense they should be.

Steven Pressfield: Oh.

Steven Pressfield: Well, I feel better.

Andrew Huberman: It's almost like a knife that's getting sharper and sharper. You can cut deeper and deeper.

Steven Pressfield: Ah. Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: Whereas at the beginning, we have sort of a dull blade, and we have to route over the same path.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh, uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: So, I think this is a nervous system feature.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: And that's why it transcends physical and mental, creative and other types of works.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Oh.

Andrew Huberman: Because if you talk to great musicians, they're not practicing 11 hours a day anymore.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: They're practicing for three or four extremely focused hours, sometimes divided up by naps and meals.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: So, in any case...

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: Huh. Very interesting.

Andrew Huberman: So, you put in your two very focused hours, with some laundry in between.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: And then you rack it. You hang it up, and you don't look at it. Are you thinking about it throughout the day?

Steven Pressfield: No. But like we were talking about, if an idea comes to me and I grab my phone and I dictate that. And let me say one thing here for anybody that's listening to this and would be, want to be writers, aspiring writers. So, I'm a full-time writer. I don't have another job. I don't have to do anything. But yet, I can only get two hours at a time basically in a day.

Steven Pressfield: So, if you guys have a full-time job, and kids, and a family, and a wife, and a spouse, whatever, if you can squeeze out a couple of hours a day, you're on the same level with me, the same level with a full-time writer. So, it is possible to have a full-time job and still do your artistic thing to a full-tilt version.

Andrew Huberman: Excellent point. How important do you think it is for you to start that writing session at more or less the same time each day? You're not saying two hours in the morning, or two hours in the evening, two hours in the morning, or an hour in the morning, hour in the afternoon. It sounds like it's very regimented.

Steven Pressfield: It is. I think it's really important. And when life was more predictable for me, I would always do it. But since the fires and other things like that, sometimes I have to shift time frames around and be ready to do that, you know?

Steven Pressfield: I have a good friend, Jack Carr, the thriller writer who did "The Terminal List," and he's a master of writing in airplanes, and writing at Starbucks, because he's always traveling and doing all kinds of stuff and just finding the time. God bless him. I don't know how he does it. And he is incredibly productive. I don't know if I could do that. Maybe I will shift from writing from 11:00 to 1:00, to writing from 1:00 to 3:00, but that's about the most variance I can put into it.

Andrew Huberman: Do you have your phone in the room when you write? And is the internet engaged on your computer when you write?

Steven Pressfield: Not at all. No.

Andrew Huberman: Both of those are...

Steven Pressfield: I mean, my phone is there maybe to dictate a note or something like that.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: But otherwise, no. Absolutely not. And, yeah, I can't even imagine that.

Andrew Huberman: Music?

Steven Pressfield: No. No music. No.

Andrew Huberman: Just the sound of your own breathing.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah. What's that?

Steven Pressfield: Because you're in your own head, right? You're in that universe, you know?

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. This is what I find so odd about writing, is you're in your head, it's your voice in your head, but you're in a conversation with the potential audience. What is the actual dialogue? Are you thinking... This gets a little philosophical, but at the end of the day, it's very concrete.

Andrew Huberman: Are you thinking about a conversation with the audience, or are you just translating thoughts into words and the audience doesn't exist yet?

Steven Pressfield: I'm very aware of the reader in the sense of... Let's say it's a scene that I'm writing, and I know certain things have to happen in this scene. Character A has to do something, Character B, da, da, da, da. And so, I'm trying to put that down, but I'm thinking, "Is the reader understanding? Have I got this in the right order for them? Am I boring them? Did I say that two pages ago, and now I'm repeating myself?

Steven Pressfield: But I'm not having a conversation. I'm just trying to make it as easy, and as interesting, and as fun as I can for the reader. And always, I'm trying to make sure that I'm leading them. I'm seducing them. I'm trying to reel them in, and not bore them, you know?

Steven Pressfield: By the end of this chapter or scene, I want the reader to be thinking, "Oh, I can't wait to turn the page and see what happens next."

Andrew Huberman: Growing up, were you a storyteller among your friends?

Steven Pressfield: No. I never even thought about it as a kid.

Andrew Huberman: Like, hanging out with friends, you wouldn't tell a story about what had happened three days ago?

Steven Pressfield: No. I mean, just like anybody else would. But no, I was never a storyteller, or anything. I was not a kid that wanted to be a writer. I never thought about it at all.

Andrew Huberman: Hmm. So, you just kind of tripped and fell into all this?

Steven Pressfield: I mean, my first job was in advertising in New York City, right out of college.

Andrew Huberman: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: This is like the "Mad Men" thing.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: But I guess at the time I thought, "Oh, I'd love to write a commercial that people said, 'Oh, that was great. It was so funny. I loved that thing.'" So, that sort of got me kind of a little bit started into the idea of storytelling. And then I had a boss, his name was Ed Hannibal, and he wrote a book kind of at home, and it became a hit, you know? And it was called "Chocolate Days, Popsicle Weeks," and he quit to become a novelist.

Steven Pressfield: And so I thought, "Well, s***, why don't I do that?" You know? So, that was what sort of started me into it, being completely naive and totally stupid, and having no idea of what I was doing.

Andrew Huberman: That's wild. So, I imagined you as the kid who was always coming in, telling stories, and you were writing in the background.

Steven Pressfield: No, not at all.

Andrew Huberman: Advertising's pretty interesting, though, because it's the same process. You have to get into the mind of the audience. You have a story to tell. And I guess with advertising the goal is a purchase, and with writing, the idea is they buy into the next page.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Something like that.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, yeah. Very similar in that sense, you know?

Andrew Huberman: Any ads that you recall particularly enjoying working?

Steven Pressfield: No, I was terrible. I was never any good at it. You know, I never made any money. I was never successful at all. But I met a lot of nice people, and I learned a lot of stuff in that.

Andrew Huberman: You said that was in New York City?

Steven Pressfield: It was in New York City. In fact, if I can hype one of my books, it's a small follow-up to "The War of Art" called "Nobody Wants to Read Your S***." And a lot of it is about what you learn in advertising, because nobody wants to read your ads, or listen to your commercials, or anything like that.

Steven Pressfield: And so, one thing you learn in that business is to make it so good, or so interesting, so intriguing, that people will overcome their hatred of having to listen to your stupid Preparation H commercial. So, anyway, that was what got me started. But I was never a storyteller as a kid. No.

Andrew Huberman: I'd like to go back to the quote that we started with. "The more important to your soul's growth, the stronger the resistance will be." I think many people will hear that, including myself, and will think, "Okay, what is my soul's growth? Where does it want to go?" You know, I think when we hear the words "soul" and "growth," particularly when it's about us, we think there's going to be this big sign written on the heavens about what we're supposed to do, and we're going to feel compelled to do it.

Andrew Huberman: You're saying the opposite, that the thing that we need to do most sometimes is hidden from us. The muse perhaps can reveal that, and it's through the act of writing, without knowing what the work even is, that sometimes we arrive there. So, for people that don't have a crystallized idea yet, and they want to explore their creative sense.

Andrew Huberman: They might want to do it through writing, they might want to do it through pottery, they might want to do it through music, they might want to do it through making movies, any number of things. What's the translation from "the thing you need most is the thing you're resisting most" to actually getting into the process of evolving that thing out of us?

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: It sounds like an extrusion process, like you're trying to push semi-solid concrete through a filter, but I want to know what the filter is.

Steven Pressfield: It's a great question.

Steven Pressfield: I mean, I know that young people today, there's a tremendous amount of pressure on people to find their passion, and follow their passion, and so on and so forth. And I know, for me, as a young person, I would go, "What the f*** is that? I don't know what it is that I want to do," you know? "I'm lost. I'm just struggling." But I do think that we are all born with some sort of a, at least one, a kind of calling of some kind.

Steven Pressfield: And it may not be the arts. You know, it may be helping other people through some kind of a nonprofit or something, or like what you're doing, Andrew, where you're bringing neuroscience and the scientific to personal development, and so on and so forth. I think we do all have some sort of calling, and we know it.

Steven Pressfield: Like, if we could somehow put somebody in here and say, "I'll give you three seconds, tell me what you should be supposed to be doing." It will pop into somebody's head. You know, they go, "Oh, I know I've always wanted to be a motorcycle..." Whatever, you know? But then that sort of whisper urge to do this thing is immediately countered by this force of resistance, because it's trying to stop us. It's the devil. It's trying to stop us from being our true selves and becoming self-realized, self-actualized, or whatever.

Steven Pressfield: So, resistance will immediately say to us... Like if you were to say, "Oh, I want to have a podcast and I want to talk about science." Immediately resistance would say, "Well, who are you, Andrew, to do this thing? I mean, you're a professor at Stanford. You don't have any experience doing this. Not to mention it's been done a million times by other people. They've done it a thousand times better than you. Nobody's going to give a s***. You're going to put this out there, you're going to embarrass yourself. You had a certain level of prestige at Stanford, now you're an idiot." It's going to be that voice, right?

Andrew Huberman: And some people actually said, "Stanford's not going to like it. Why would you do this? You're tenured at Stanford. What are you doing? You're funded, and your lab's publishing well." One of those people was my father, who's also a scientist. My process of pushing back on that...

Steven Pressfield: I rest my case.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: And the true part here, the really kind of interesting part, is a lot of times those voices will be the voices closest to us. Our spouse, our father, because... Well, I can get into that. I'll get into that if we want to continue. But in any event, so that voice of resistance will come up. In addition, resistance will try to distract us. It'll try to make us procrastinate. It'll try to make us yield to perfectionism, where we noodle over one sentence for three days, or fear, all of the other things will stop us.

Steven Pressfield: So, many people live their entire lives and never enact their real calling, you know? But we were talking about the more important to the growth of your soul, that was what we started with this, right?

Steven Pressfield: So, that calling, whatever it is, to be a writer, a filmmaker, or whatever it is, if we don't do that in our life, that energy doesn't go away. It becomes... It goes into a more malignant channel, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: And it shows itself in maybe an addiction, alcoholism, cruelty to others, abuse of others, abuse of ourselves, porn, you name it.

Steven Pressfield: Any of the sort of vices that people have, because that original creative divine energy that really wants to be the "Odyssey" or something like that, if we yield to our own resistance and don't evolve that, then bad things happen.

Steven Pressfield: On the other hand, if we do follow that, we kind of open ourselves up to becoming who we really are. And a lot of people in podcasting, and the human development, or whatever they call it, personal development world, they sort of promise like some sort of nirvana is going to happen if you do X, Y, Z.

Steven Pressfield: But what I'm promising is a f*** of a lot of hard work that's probably never going to be rewarded, but you'll be on the track that your soul was meant to be on. And God bless you. You can't ask for any more than that.

Andrew Huberman: And sometimes it works out at spectacular levels of whatever, income, fame, whatever it is that people think they might want, but that's not really the thing to chase.

Steven Pressfield: Right.

Andrew Huberman: We'll talk about that.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah, we'll talk about that. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: So, sometimes it's the lottery of life.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Sometimes. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Sometimes. But that absolutely should not be the thing that people are chasing.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah. I only know my own experience, and I couldn't help but reflect a little bit on when I was deciding to do the podcast, and I did get some voices back like, "Hey, maybe that's... What are you doing?" I'm not clinically diagnosed with Tourette's or anything like that, but I felt at that point that I had a certain amount of knowledge in me, based on 25 years of studying and research in neuroscience and related fields. And I felt like if I didn't let it out, I was going to explode.

Steven Pressfield: Ah. Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: And so, Rob, my producer, and my bulldog, Costello, and I went into a small closet in Topanga, and set up some cameras, and I exploded onto the camera.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: It just poured out. I think for the entire first year, we were doing almost all solos, hardly any guests, because it was a pandemic, and we weren't quite yet sitting down with guests.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: Oh, I didn't know that.

Andrew Huberman: And I don't even remember thinking about the hundreds of hours of preparation. We did hundreds of hours of preparation for each episode. But the just... I just feel like it just kind of geysered out. So, I think there's some benefit to having something build up so much within us that it has to come out.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: And I can certainly relate to the dangers of suppressing something. I think that you...

Steven Pressfield: And how old were you when you started that?

Andrew Huberman: Forty-five years old.

Steven Pressfield: Forty-five. Ah. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, so I was kind of late to it. Now, I had lectured in front of students and given seminars, and lectured in front of donors, which is in some ways similar to the podcast in the sense that you're teaching science often to non-scientists or diverse fields.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: But, for me, it was just inside. I couldn't help it.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: My only answer was I couldn't help it. And to his credit, by the way, my dad has been immensely supportive of the podcast.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: He actually was on the podcast.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: And gave us a chance to bond and learn about him.

Steven Pressfield: Oh, that's great.

Andrew Huberman: And he's a scientist, so I got to learn some physics. The audience got to learn some physics as well.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: But, yeah, when you take on something that people are not familiar with you doing, or they are projecting onto you the sense that they want you safe and secure, because sometimes it's a real, it's a genuine kind of feeling of support for somebody, you know?

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: A mother, or father, or siblings like, "Hey, so you're going to give up your job as a lawyer to go write movie scripts?"

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: And you got three kids, and they're scared for you because they don't want to see you take your life off a cliff.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: What's your response to that?

Steven Pressfield: I mean, there's validity to that, obviously.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: But I think what happens is that each person is dealing with their own resistance, their own calling, that they know that they really should be doing, and 99.999% of them are not doing it, or are unconscious of it, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: It's sort of a niggling thing, but they don't know about it. So, then when they see you, Andrew, starting your podcast, that's a reproach to them. And they say, "Well, if Andrew can do it, why can't I do it?" You know? And so, then it becomes kind of malicious. And I don't think it's deliberately malicious a lot of times, but people will then try to undermine you and say, under the guise of, "We're only looking out for you. We don't want your children to be starving and in the street," they will try to undermine you and stop you from doing it, and make fun of you or ridicule you. Like the filmmaker David O. Russell. I don't know if you know who I'm talking about. He did "The Fighter" with Mark Wahlberg.

Andrew Huberman: I love that movie.

Steven Pressfield: He did "Silver Linings Playbook," with Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper.

Andrew Huberman: I did not see that one, but I did see "The Fighter."

Steven Pressfield: And "Joy," about the lady who invented the Miracle Mop, which was Jennifer Lawrence.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: And all of these stories are about sabotage by the people closest to you, particularly your family.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Like in "The Fighter," Mark Wahlberg is this boxer, right? And he's got seven sisters, and he also has an older brother, and they're like... And his mom is his manager, and she's booking him fights where he's outweighed by 20 pounds and he gets massacred, you know?

Andrew Huberman: True story of Micky Ward.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Right. Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: And the story is he finally meets a girl who's really supportive of him. But anyway, it's a real theme that the people closest to us will try to... They don't want us... They're happy the way, you know, "We like you, Andrew, the way you are." You know, "Our son, we know he's working at Stanford, he's doing his thing, we don't want to see him..." It may be unconscious. I'm not knocking your dad. "We don't want to see him suddenly burst out of the cocoon and become a butterfly and wing away from us," you know? So, they like you the way they are, you know. The way you are.

Andrew Huberman: We've known for a long time that there are things that we can do to improve our sleep, and that includes things that we can take, things like magnesium threonate, theanine, chamomile extract, and glycine, along with lesser-known things like saffron and valerian root. These are all clinically supported ingredients that can help you fall asleep, stay asleep, and wake up feeling more refreshed. I'm excited to share that our longtime sponsor, AG1, just created a new product called AGZ, a nightly drink designed to help you get better sleep and have you wake up feeling super refreshed.

Andrew Huberman: Over the past few years, I've worked with the team at AG1 to help create this new AGZ formula. It has the best sleep-supporting compounds in exactly the right ratios in one easy-to-drink mix. This removes all the complexity of trying to forage the vast landscape of supplements focused on sleep, and figuring out the right dosages and which ones to take for you. AGZ is, to my knowledge, the most comprehensive sleep supplement on the market.

Andrew Huberman: I take it 30 to 60 minutes before sleep, it's delicious, by the way, and it dramatically increases both the quality and the depth of my sleep. I know that both from my subjective experience of my sleep, and because I track my sleep. I'm excited for everyone to try this new AGZ formulation, and to enjoy the benefits of better sleep. AGZ is available in chocolate, chocolate mint, and mixed berry flavors. And as I mentioned before, they're all extremely delicious. My favorite of the three has to be, I think, chocolate mint, but I really like them all.

Andrew Huberman: If you'd like to try AGZ, go to drinkagz.com/huberman to get a special offer. Again, that's drinkagz.com/huberman.

Andrew Huberman: Today's episode is also brought to us by Rorra. Rorra makes what I believe are the best water filters on the market. It's an unfortunate reality, but tap water often contains contaminants that negatively impact our health.

Andrew Huberman: In fact, a 2020 study by the Environmental Working Group estimated that more than 200 million Americans are exposed to PFAS chemicals, also known as forever chemicals, through drinking of tap water. These forever chemicals are linked to serious health issues, such as hormone disruption, gut microbiome disruption, fertility issues, and many other health problems. The Environmental Working Group has also shown that over 122 million Americans drink tap water with high levels of chemicals known to cause cancer.

Andrew Huberman: It's for all these reasons that I'm thrilled to have Rorra as a sponsor of this podcast. I've been using the Rorra countertop system for almost a year now. Rorra's filtration technology removes harmful substances, including endocrine disruptors and disinfection byproducts, while preserving beneficial minerals like magnesium and calcium. It requires no installation or plumbing, it's built from medical-grade stainless steel, and its sleek design fits beautifully on your countertop. In fact, I consider it a welcome addition to my kitchen. It looks great, and the water is delicious.

Andrew Huberman: If you'd like to try Rorra, you can go to rorra.com/huberman and get an exclusive discount. Again, that's Rorra, R-O-R-R-A.com/huberman.

Andrew Huberman: We've had several clinical psychologists on the podcast, and a resounding theme from them has been that it is astounding, and yet consistent, that people will remain in a not-so-great place that they understand and is predictable in exchange for what they could do, stepping into some new life, even getting over their anger about something.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: In fact, I was thinking throughout today's conversation, I couldn't help but think that perhaps the two most dangerous things to the creative process, to really doing the important work, are the many, many things that exist in the world now that basically sell us the opportunity, for free, to be angry, or to numb out.

Steven Pressfield: Mm, mm.

Andrew Huberman: I mean, again, if people want to drink a little bit, I'm not going to disparage that. I've done an episode on alcohol.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: It's not good for you, but some people can have a couple drinks a week or whatever. Okay, not judging there. But things like alcohol, like certain forms of social media. And I say certain forms, because I do think social media can be informative and educational in the right context, and in the right amount.

Andrew Huberman: Certain forms of media more generally, the news, right? Any number of highly processed, highly palatable foods, which are not delicious, but they allow us to kind of numb out, numb out our senses, and just kind of mindlessly eat, and on and on.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: I feel like anger and numbing out are how the world is trying to pull us away.

Steven Pressfield: Mm.

Andrew Huberman: And someone gets paid for that. We think we get it for free, but they get paid for that very well.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: We give our time, our soul, according to what you're saying.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: And then more close to us, within our inner circle, people that genuinely care about us are, from what you're saying, kind of in their own psychological entanglements, and they really care, they want us safe, they want to keep us where they know they can find us. And as a consequence, it's really tough to even get to the process of resistance at this point. It's all around us.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: It's all around us.

Steven Pressfield: You hit the nail on a lot of heads there. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: So, do you think the world is set up now in ways that it's more difficult to get to that chair and to meet the inner resistance? I phrased it poorly before. There's resistance all around us, there's in the things that are being sold to us, quote unquote, "for free."

Steven Pressfield: Mm.

Andrew Huberman: The cost is immense.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: It's true, you're not putting a coin in a slot and pulling a lever, but it's your time, it's your soul, it's your essence, it's your life.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: And then it's close to us with family members and friends, and significant others sometimes. Dogs are immune from this. Cats are immune.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh. Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: They want us to do the real work because they'll be right next to us.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: And then with all that, then we sit down, and then the resistance comes up from right up in the middle.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: It's like this is a minefield.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. It is. I agree with you completely. I don't think it's ever been harder. I always said that if you want to make a billion dollars, come up with some kind of product that feeds into people's natural resistance, like potato chips, or social media, or something. And they did come up with a product and it's called the internet, you know? It's called social media. And you're right.

Steven Pressfield: People make a lot of money off of that because they... And I don't think they're even aware of what they're doing, or aware of what they're tapping into, but they're just allowing people, you or me, who has a calling that we know we should be doing, they're allowing us to not do it, to be drawn over here for whatever reason. And I think a lot of the anger and polarization in politics is about that today, you know? Because people can't face to sit down and do whatever they were born to do.

Steven Pressfield: So, it's much easier to hate the other person over here, or get completely caught up in all that rabbit hole of all that sort of stuff, you know? Yeah. To follow your calling is a really hard thing, you know? We were born to be, by evolution, to be tribal creatures, through all this evolution.

Steven Pressfield: And the one thing that the tribe hates the most is somebody that goes his own way or her own way, right? Follows their own thing and doesn't hue to what the tribe wants them to do. So, for us to do that as individuals is a b****, you know? And it's usually like when you said you sort of exploded out of you when you got... You have to almost reach a breaking point, you know?

Steven Pressfield: Almost hit bottom in some kind of a sense before it just kind of explodes out of you, because we'll all resist that so much. It's so scary.

Andrew Huberman: It's so interesting. I think it was in high school that I first realized how silly humans are, and it was the following. At the time I was into skateboarding.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Skateboarding has gone through various evolutions of being popular, now it's in the Olympics, of being unpopular, of being profitable. When I got into it, it was really unpopular. It had gone through two big waves. There was the kind of "Dogtown and Z-Boys" wave, discovering backyard pools, this kind of thing that the surfers did.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Then there was a second wave, for those that care, this was like the classic Bones Brigade wave. There were only two or three big companies. Tony Hawk was early in this because he was young.

Andrew Huberman: His dad, Frank Hawk, ran the National Skateboard Association. And then it disappeared. Just kind of kids that were into soccer, they were into other sports, skateboarding wasn't a big thing. It was small. And then there was this really kind of weird trend in the early 90s where skateboarders started wearing really baggy clothes. No one wore really baggy clothes.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: And I'll never forget, because I was part of that community, we wore these, what now wouldn't even be considered baggy shorts. So, we're not talking about, like, a deep sag on the shorts, but it was like baggy shorts.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: And I'll never forget the amount of teasing and ridicule that we received. People were like, "Pull up your pants."

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: By the athletes, by the water polo athletes, the jocks, everything.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: But not just at school, but elsewhere. Leave for the summer, come back, and over that summer, someone in the world of rock and roll and in hip hop had kind of picked this up from skateboarding culture, and baggy pants and shorts hit the mainstream.

Steven Pressfield: Oh, I never knew that.

Andrew Huberman: And the next year, everyone was into that.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: And that's when the bell went off. I was like, "They don't actually know what they like." This is just the essence of peer pressure. They have no concept of what they actually like.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: And I think that was a big one for me. Well, first of all, I thought, "They're hypocrites."

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: Then I thought, "They're idiots." And then I realized they're none of those things. It's that for most people, what they like is sold to them.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: And they're tracking someone else. And so, throughout my life, I've had mentors that didn't know me. I literally have a list of different names, some of these people are alive, some of them dead. Amazingly, some of them are now my close friends.

Steven Pressfield: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: I embarrass them all the time by telling them that they're on this list.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: But I think that the concept of mentorship is so much different than the concept of looking to the other members of our species more broadly for what is cool, what's worth pursuing.

Steven Pressfield: Mm.

Andrew Huberman: How valuable, for you, have mentors been? I know you've been a mentor to many people. By the way, you're on the list. Just to embarrass you. I can show you that list.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. [unintelligible]

Andrew Huberman: From the late 90s, 2000s transition, how important are mentors, and how do we differentiate mentors from the voice in our own head? How important is it to be self-guided versus encouraged and guided by these mentor voices?

Steven Pressfield: Well, that's a great question.

Andrew Huberman: Because I believe that the general public is the absolute wrong signal. I think that signal takes you off the metaphorical cliff.

Steven Pressfield: I agree with you there.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Steven Pressfield: Yeah. Mentors have been really important to me, very important. In fact, I wrote a memoir called "Govt Cheese." I don't know if you've heard about this one at all. But the chapters are named after the various mentors that I've had, many of them. And a lot of them are not in the writing world at all. Like my friend, Paul, he was in the writing world.

Steven Pressfield: But I had a boss at a trucking company that I worked for that was like a real mentor to me. I picked fruit in Washington State, as a migratory worker, for a while, and I had a mentor there. I never even knew his last name. He was a fellow fruit picker, a former Marine, who was at the Chosin Reservoir in Korea. I'm sure nobody listening to this knows what that is, but it was like an amazing horror show of heroism. Anyway.

Andrew Huberman: They'll look it up.

Andrew Huberman: What was it about those two mentors that you can maybe summarize that you extracted? Was it a work ethic? Was it a style of being?

Steven Pressfield: It was a work ethic in both cases. In the one... Again, I'll sort of get a little into the weeds here a little bit.

Andrew Huberman: Please, please.

Steven Pressfield: I had gone to a tractor-trailer driving school, and I got hired to work for this company in North Carolina, and I was a beginner. And I really f***** up big time one time. I dropped a trailer with like 300,000 dollars' worth of industrial equipment in it.

Steven Pressfield: And my boss, his name was Hugh Reeves, took me out to this hot dog place called Amos "N" Andy's in Durham, North Carolina, and he sat me down and he said, "Son, I don't know what internal drama you're going through. I know you're going through something. But let me tell you this. While you're working for me, you're a professional, and your job is to deliver a load.

Steven Pressfield: And I don't care what happens between A and B; you got to do that." And I was like, "Well," you know. And I knew he was just absolutely right, and I thought, "Man, I got to get my s*** together here," you know? And so, that obviously stuck with me forever.

Steven Pressfield: And my friend, John, from Seattle in the fruit-picking world was... Again, I'm going to do a longer story than probably needs to be here. In the fruit-picking world, at least when I was doing this, most of the work was done by fruit tramps, by guys that were riding the rails from the old days. And one of the phrases that they used was "pulling the pin." Have you ever heard this thing? And what "pulling the pin" meant was quitting too soon.

Steven Pressfield: "Pulling the pin" came from railroad, if you wanted to uncouple one car from another, the trainman would pull a heavy steel pin, and the cars would uncouple. So, you would wake up one day in a bunkhouse at six weeks into a season and so-and-so would be gone and you'd say, "Oh, what happened to Andrew?" And they'd say, "Oh, he pulled the pin." So, at the time that I was there, I was trying for the first time to finish a book. And I'd run out of money and this is why I was working, to get the money.

Steven Pressfield: And I realized that in my life, I had pulled the pin on everything that I'd ever done. On my marriage, on this, that, the other. And this friend of mine, John, I wanted to quit before the season ended, you know? And he would not let me do it, you know? He sort of just took me under his wing. And so, that was another thing which is drilled into my head in the sense of, "Am I going to finish this project? F*** yeah. I'd rather die; I will die before I'll give up on this project." And it was all because of him.

Steven Pressfield: So, those are two mentors that weren't writing mentors, but that I used their... Those lessons stuck with me forever. And I will say one thing, too, for anybody that's struggling with finishing anything. Once I did finish that book, which I did, I've never had any trouble finishing anything ever again.

Andrew Huberman: Hmm.

Steven Pressfield: Whereas it was my bête noire for years. I would fumble on the goal line, you know? Resistance, form of resistance.

Andrew Huberman: I love that those two guys are now alive and present in 2025.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: They may still be alive, in general. But perfectionism. You talked about it as the enemy. I learned two very disparate schools of thought in research science. One was no one study can answer everything. So, when you get to the point where you have a clear answer what the data mean, you write it up, you ship it out, you publish.

Steven Pressfield: Uh-huh.

Andrew Huberman: And I feel very fortunate that I worked for people that encourage that, because many people get caught up in the idea that every paper has to be a landmark paper. Actually, that's one of the major causes of scientific fraud, by the way.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: When people feel that their papers have to be published in the top-tier journals.

Steven Pressfield: Ah.

Andrew Huberman: It's probably the strongest driver of scientific fraud.

Steven Pressfield: Makes sense.