How to Set & Achieve Massive Goals | Alex Honnold

Listen or watch on your favorite platforms

My guest is Alex Honnold, a professional rock climber considered by many to be one of the greatest athletes of all time for his historic free solo (no ropes or man-made holds) ascent of El Capitan in Yosemite. We discuss how to envision massive goals in any part of life and the process of breaking down those goals into actionable daily steps. Alex shares how embracing your uniqueness and mortality is the most powerful way to envision and live a fuller, more intentional life. We also discuss strength and endurance training, assessing risk and how Alex prepares mentally and physically for extreme challenges. We also discuss how to balance goal-seeking with family and work. Regardless of your goals, profession or age, this conversation will very likely reshape how you think about and approach your life, goals and potential.

Books

- Open: An Autobiography

- The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life (Learn In and Use It for Life)

Resources

- Free Solo

- Meru

- Girl Climber

- Yosemite National Park

- El Capitan

- Moonbow at Yosemite Falls

- Weighted vest (Omorpho)

- It’s not glue, suction or static electricity that keep geckos from falling off the ceiling

Huberman Lab Episodes Mentioned

- Pavel Tsatsouline: The Correct Way to Build Strength, Endurance & Flexibility at Any Age

- Dr. Erich Jarvis: The Neuroscience of Speech, Language & Music

- How to Increase Your Speed, Mobility & Longevity with Plyometrics & Sprinting | Stuart McMillan

People Mentioned

- Michael Muller: American photographer

- Twyla Tharp: American dancer, chorographer

- Tony Hawk: American skateboarder

- Tommy Caldwell: American rock climber

- Ken Block: American rally driver, stuntman

- Peter Croft: Canadian rock climber, mountaineer

- Danny Way: American skateboarder

- Tom Bilyeu: American entrepreneur, filmmaker

- Ryan Holiday: American author, media strategist

- Emily Harrington: American rock climber, mountaineer

- Evel Knievel: American stunt performer

- Hunter S. Thompson: American journalist, author

- Mike Mentzer: American bodybuilder

- Dorian Yates: English bodybuilder

About this Guest

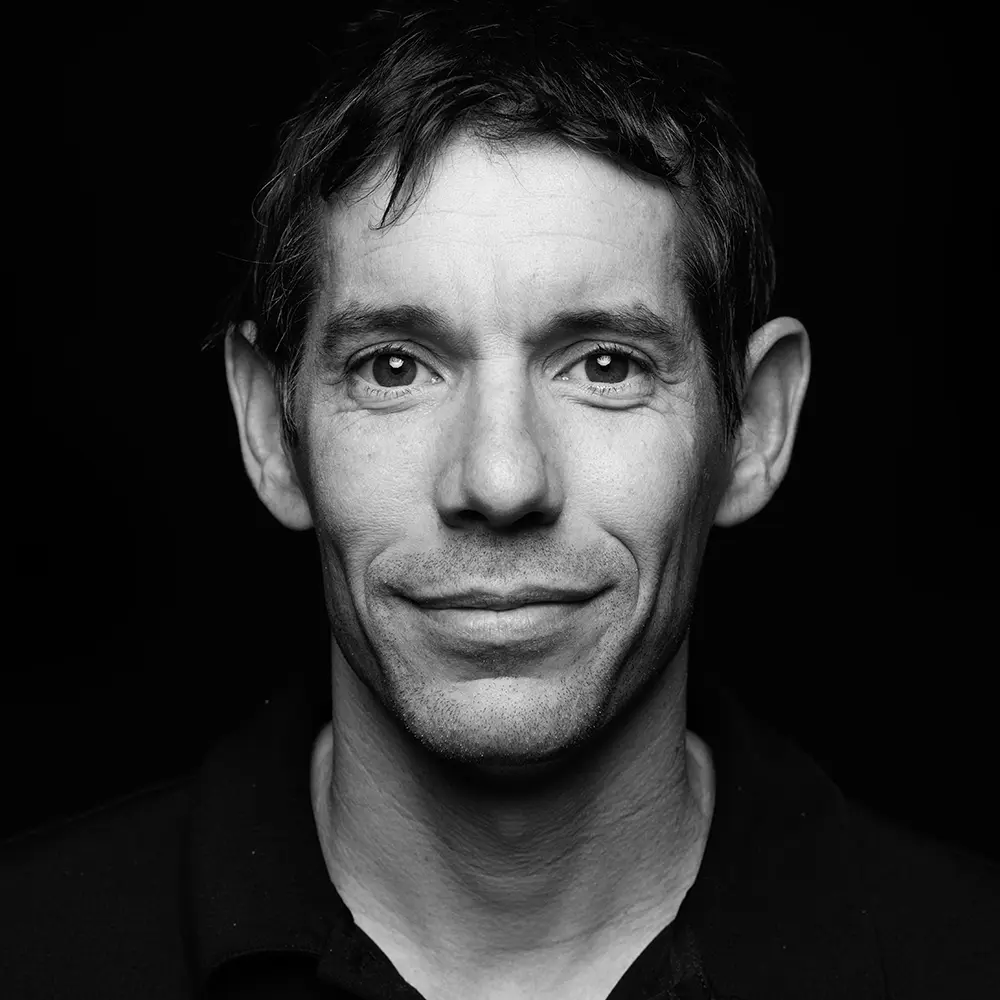

Alex Honnold

Alex Honnold is a professional rock climber considered by many as one of the greatest athletes of all time for his historic free solo (no ropes or man-made holds) ascent of El Capitan in Yosemite.

This transcript is currently under human review and may contain errors. The fully reviewed version will be posted as soon as it is available.

Andrew Huberman: Welcome to the Huberman Lab podcast, where we discuss science and science-based tools for everyday life.

Andrew Huberman: I'm Andrew Huberman, and I'm a professor of neurobiology and ophthalmology at Stanford School of Medicine. My guest today is Alex Honnold. Alex Honnold is a professional rock climber.

Andrew Huberman: He's best known for successfully free soloing, meaning climbing with no ropes or latching on of any kind, El Capitan, also called El Cap, which is a nearly 3,000-foot climb in Yosemite National Park. It was also, of course, the topic and focus of the incredible movie "Free Solo," which if you haven't seen, you absolutely should watch. I've wanted to talk to Alex for a long time now. I'm not a rock climber. I've tried it a few times. But I've been extremely curious to understand Alex's mental frame around learning and training and his broader philosophy on life.

Andrew Huberman: My interest stems from the fact that Alex's free solo of El Cap, and his other climbs make him one of the most accomplished and innovative athletes in all of history. And of course, the free solo of El Cap is extremely high-risk and high-consequence. Today, we discuss how to envision and make progress towards your goals and how to merge the demands of daily work and family life with incremental training for spectacularly big or long challenges of any kind.

Andrew Huberman: Alex makes clear that it's essential and possible to build your capacity to exert effort and how to do that in a regimented way so as to bring seemingly impossible goals within your reach. We also discuss how coming to terms with one's own mortality is actually one of the best motivators for building a great life and why most people hide from that reality, and as a result, end up living much smaller lives than they otherwise would. We also discuss training, literally what to do to build strength and endurance, not just for sake of rock climbing, but just generally.

Andrew Huberman: And that takes us into discussions about weight training, body weight training, running, hiking, and a bunch of other things that you can apply. Even if you have zero interest in rock climbing, today's conversation with Alex Honnold will definitely change the way that you think about your life, what you can make of it, and how to go about that. Before we begin, I'd like to emphasize that this podcast is separate from my teaching and research roles at Stanford. It is, however, part of my desire and effort to bring zero-cost-to-consumer information about science and science-related tools to the general public. In keeping with that theme, today's episode does include sponsors. And now for my discussion with Alex Honnold.

Andrew Huberman: Alex Honnold, welcome.

Alex Honnold: Thanks for having me.

Andrew Huberman: I think Free Solo is remarkable for a ton of reasons, but as a good friend of mine, who I think you know, Michael Muller, photographer, he said, before I'd seen the film, he said, "It's wild because you're terrified as an observer the entire time, but you also know that Alex survives from the very beginning." Which is a very unusual-

Alex Honnold: But I think some people don't know that.

Andrew Huberman: Oh, really?

Alex Honnold: Some people watch the movie and they literally have no idea what it's about or what's going on, and they spend the whole movie being like, "Oh, my God, what's going to happen?"

Andrew Huberman: Okay, so I just spoiled it.

Alex Honnold: I think-- Oh, yeah, yeah. Well, at this point, I'm like, "Nobody cares. It's old news."

Andrew Huberman: Well, it's a spectacular feat, and we can go into that feat, but I'd actually like to drill in a little bit to just your process in general. I'm sure that's changed over time, and feel free to talk about that. But, you know, I'm very curious about sort of notions of intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation, right? And I think Free Solo is also remarkable because you had cameras on you. It was obviously to be recorded, and you knew you had cameras on you.

Andrew Huberman: And yet, I always thought of climbing as kind of a solitary sport, or things that people do in small groups kind of off the grid. Things have changed now with social media, the way everything can be posted very quickly or even run live. But when you think about sort of the work that you're doing in terms of progressing and goals and kind of milestones for yourself, how do you envision that? Is this in like a-- Do you have a diary? Do you have a process where you sit back and you think, you know, "What would be awesome for me to experience?

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Would people like to see it?" What's the sort of balance between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for you?

Alex Honnold: So basically, I think climbing is always intrinsically motivated. I mean, I started climbing when I was a child. I've always loved climbing. I love the movement of climbing, I love the feeling of it, I love the whole experience, you know, and just everything about it's great. But then, you know, now as a professional climber, obviously there is that extrinsic motivation as well where you're like, "Oh, this is how I make a living." And so I think with the film "Free Solo," it was a really interesting balance of the two where it's like, this is something that I'd love to do for myself and even if no one else in the world existed, I'd want to do this thing.

Alex Honnold: But then you also know that if the film turns out well, which it did, you know, it's going to be great for your career, it's going to be great for whatever. And so, like, there is that extrinsic motivation as well. And so then you're always trying to parse out, like, which part is which, and, you know, because you don't want to... particularly with free soloing, you don't want to be too extrinsically motivated because you don't want to get pushed into something that you're not prepared for or that you shouldn't be doing.

Alex Honnold: Of course, you know, even being intrinsically motivated, you can do something you shouldn't. I don't know, I mean, but you're just constantly thinking about those things as a climber.

Andrew Huberman: In order to free solo El Cap, did you memorize sequences or is it more sort of like motifs where you kind of know that you're going to do any number of different things in a given pitch?

Alex Honnold: It depends. So for the hardest parts, I memorized, like for sure, memorized every aspect of it. But that's only the hardest part, so that was maybe like a third of the route. And then for the easiest third, and some of it is actually quite easy. Some of it's like even a non-climber could climb small sections of the wall. Like, there are parts that are quite easy here and there. You know, it's like not the bulk, but so for the easy parts, you just know that you can do it and you don't have to stress it.

Alex Honnold: And then the medium parts, kind of, like, the remaining third of the wall, you sort of remember, kind of like you said, motifs. You might know the hardest part and you just kind of know that it's going to be fine, but you don't have to memorize it per se. But certainly, I knew the route very, very well. You know, you just know all the things that you have to know.

Andrew Huberman: You recognize not just holds, but, like, visceral sensations, like this feels different or-- Because I imagine conditions change, right? I mean, weather conditions, heat on the rock shadows on the rock.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, but not as much as you might think because I was only climbing it in shade. Like, in the springtime, that whole west side of the wall stays in the shade until 11:00 or noonish in the morning. So, you go at 4:00 in the morning and then you have sort of eight hours of solid shade. So normally, the temperature and the conditions feel relatively stable. And you spend the whole season working on it, so you kind of know that tomorrow's going to feel the same as it did today, roughly, you know? And so, it's all within a relatively narrow band.

Alex Honnold: Particularly in the spring, which is why I did it in the springtime. In the fall and the autumn, it's a little bit different because the sun is lower in the sky, so it gets sun much earlier and it actually is way hotter, counterintuitively. It's, like, colder when it's in the shade but then hotter when it's in the sun. And anyways, that makes it harder for climbing, obviously. But when I free soloed El Cap, I was spending three or four months a year in Yosemite every year. You know, a month or two every spring and every autumn. And so you're spending four months a year in a place, you just know how it feels, you know? It's like you're used to getting up that early, you're used to climbing on the wall and you're just kind of like, "Oh, it's going to be another beautiful day on the rock."

Alex Honnold: And actually, the day that I did the free solo of El Cap, it was actually a little more humid and a little warmer than I maybe... than would have been optimal. Like, it's not what I would have chosen. But that's just the way it was that day and I was kind of like, "Well, this is my day," you know? You kind of just have to do the thing. But it'd been, like, overcast that night. And you know when it's cloudy at night, the lows don't drop as low? And so I woke up and it was, like, kind of muggy-ish feeling. I was like, "It's not great for being 4:00 in the morning." It feels kind of gross. But I was like, "This is my day," and it was fine.

Andrew Huberman: So you form a relationship with the rock, you kind of like learn to recognize its different states. When you did it and completed it, because I know you set out one day and then you called it off.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, that was in the autumn.

Andrew Huberman: Okay.

Alex Honnold: That was the season before.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And, basically the season was ending, like, storms were coming in the next week type deal, and it was like, the season was winding down. It was kind of like, "Well, I should at least take a shot," because I'd done a lot of prep and I felt mostly ready. And it turns out I just wasn't ready-ready, and so I wound up bailing. But that was kind of my end of the season, like, "I think I can squeak this in," knowing that if I couldn't squeak it in then, then I'd have to wait six more months. And with the pressure of the film crew and all that stuff, knowing that there are all these people, like, working and waiting for you, you're kind of like, "Well, I ought to at least try to get this done." because like all these people are waiting on me. But as it turns out, I just didn't quite have it yet. And then when I ultimately did do it in the spring, I was much better prepared, felt way better, the whole experience worked out better. So now in retrospect, I'm like, "Oh, I'm glad that it played out that way," because it was better. But at the time it was, you know, I was like, "Oh, God, I failed on this thing. All these people are watching, it's embarrassing." You know, it was all very stressful at the time.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, the external pressures have to be, you know pretty mighty especially when they're your friends. I guess one could imagine, like when it's just business, you can just be like, "Well, it's just business." But yeah, you had a lot of friends up there with you.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: For me, the thing is that if I'm going to go climb the wall, you know, I start climbing at 4:30 in the morning or 5:00 or something. So that means some of my friends, to get in position at the top of the wall, are getting up at, like, 1:00 in the morning and then hiking to the top of the mountain with a heavy backpack. And if you're asking a bunch of your buddies to go hiking at 1:00 in the morning, like, you better live up to your end of the thing, you know? Like, if you say you're going to do something, you better actually do the thing because your friends... Obviously, no one's complaining. No one is pressuring me, no one's-- But at the same time, you don't want to bail.

Andrew Huberman: Sure.

Alex Honnold: Like, it's pretty embarrassing if you tell someone you're going to do something and then you just can't do it.

Andrew Huberman: Well, they certainly wanted the outcome to be only one way and-

Alex Honnold: Yeah. And they were all super positive and supportive and it's all great, but you still can't help but feel that pressure.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Sure. Well, it certainly worked out. I'm curious, on a scale of one to 10, 10 being a total certainty along that trajectory, when you completed it, were there any phases where you felt you had to improvise against the original plan?

Alex Honnold: You mean on the day of the actual free solo?

Andrew Huberman: On the day of the actual completion of the free solo on El Cap.

Alex Honnold: No, on the day I was 100 percent. Everything was perfect, I knew exactly what to do, it was all amazing. But it took a really long time to get there.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: You know, it was like, literally years of building up to it and then months of preparation and everything. But no, on the day, it was perfect.

Andrew Huberman: I'd like to take a quick break and thank our sponsor, Joovv. Joovv makes medical grade red light therapy devices. Now, if there's one thing that I have consistently emphasized on this podcast, it is the incredible impact that light can have on our biology.

Andrew Huberman: Now, in addition to sunlight, red light and near infrared light sources have been shown to have positive effects on improving numerous aspects of cellular and organ health, including faster muscle recovery, improved skin health and wound healing, improvements in acne, reduced pain and inflammation, even mitochondrial function, and improving vision itself. What sets Joovv lights apart and why they're my preferred red light therapy device, is that they use clinically proven wavelengths. Meaning specific wavelengths of red light and near infrared light in combination to trigger the optimal cellular adaptations. Personally, I use the Joovv whole body panel about three to four times a week, and I use the Joovv handheld light both at home and when I travel. If you'd like to try Joovv, you can go to Joovv, spelled J-O-O-V-V, .com/huberman. Joovv is offering an exclusive discount to all Huberman Lab listeners with up to $400 off Joovv products.

Andrew Huberman: Again, that's Joovv, spelled J-O-O-V-V, .com/huberman to get up to $400 off. Today's episode is also brought to us by BetterHelp. BetterHelp offers professional therapy with a licensed therapist carried out entirely online. I've been doing weekly therapy for well over 30 years. Initially, I didn't have a choice. It was a condition of being allowed to stay in school. But pretty soon I realized that therapy is an extremely important component to overall health.

Andrew Huberman: There are essentially three things that make up great therapy. First of all, it provides the opportunity to have a really good rapport with somebody that you can really trust and talk to about essentially any issue that you want. Second of all, it can provide support in the form of emotional support or directed guidance, or of course, both. And third, expert therapy should provide you useful insights, insights that can help you improve in your work life, your relationships, and in your relationship with yourself. With BetterHelp, they make it very easy for you to find an expert therapist who you resonate with and that can provide those three benefits that come from expert therapy.

Andrew Huberman: Also, because BetterHelp therapy is done entirely online, it's very time efficient and easy to fit into a busy schedule. There's no commuting to a therapist's office or sitting in a waiting room looking for parking, any of that. You just hop online and you do your session. If you'd like to try BetterHelp, you can go to betterhelp.com/huberman to get 10% off your first month. Again, that's betterhelp.com/huberman.

Andrew Huberman: When you climb, I'm curious where your mental horizon is. I can make up a story as a non-climber that your mental horizon is always on just the next maneuver, just getting further up or further over. Sometimes, of course, you have to go down and up. But that your sort of time-bending and your space-bending is very, very close.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: But do you ever go into states where you're sort of in automaticity? I mean, we hear about flow, right? But where you find yourself kind of maneuvering as opposed to being hyper-strategic about what's happening in the next five seconds, 10 seconds?

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Well, I think the aspiration is to be in that, you know, flow state, whatever you want to call it. But, actually, I think even in the film, there's some quotes from me saying autopilot and things. Like, you know, I'm aspiring to be on autopilot.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: So, I'm aspiring to not be thinking too much about it. And that's, for me at least, why it required so much practice, was to be able to just do something almost by rote, through repetition, just to do the thing that you've practiced without having to think about it. Because I think once you start thinking about it too much, you're just more prone to not just make errors, but just, like, get too... get caught up in your own mind. And I don't know. I mean, the aspiration was just to do the thing.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Like, no thinking about it, no hesitation, you know, no emotional affect around it, to just do it.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. Is the kinesthetic aspect of it big? In other words, are you feeling your way through it, as well as using vision? I mean, I imagine that these things start to blend.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, I've actually never been asked something quite like that. And in some ways, I mean, the kinesthetic aspect is maybe the whole thing. I mean, it is kind of like dancing or something, where you are just flowing over stone. I mean, obviously, you're looking around and you're looking at your footholds, and you're sort of placing your feet correctly that way. But really, you're just doing sequences. You're just flowing. Like, your body is moving.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: I mean, I think when you climb well, and particularly when you've rehearsed something and you know the climb really well, it feels like jogging or swimming or sort of other elemental movement patterns, where it's just, like, your body doing what it's meant to do, and it feels great, you know? It's like, it's really nice.

Andrew Huberman: Do you ever surprise yourself still, like, that in training things, you know, "I'm surprised that worked out," and then stick with that kinesthetic sense? I've been listening to an amazing book by Twyla Tharp. She's a choreographer. She was a ballerina. She's a choreographer, and she said that what distinguishes, you know, sort of virtuosity from mastery is that when you start to surprise yourself.

Alex Honnold: Yeah.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: And I think you're certainly in that category of virtuoso. How often does surprise come about?

Alex Honnold: For me personally, that's maybe my favorite moment in climbing, is when you surprise yourself. And this isn't so much with free soloing, because with free soloing, you don't want to be surprised. But with a rope on, you know, you have moments all the time where you're sure you're about to fall because you're up against your physical limits or whatever, and then you stick a move that you were sure you weren't going to.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And, you know, it doesn't happen that often, but when it does, you're like, "Oh, I exceeded my own expectations." It's like the best feeling, you know? It happens from time to time.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: In some ways, actually, I was telling one of my friends, I think that that might be one of the ways in which I see aging. You know, like, as I'm getting older as a climber, I think I surprise myself less often. I think, as, like, a 24-year-old, you just don't know your own limitations that much, and you frequently surprise yourself, where I'm like, "Wow, I really outdid myself. I really did something that I was sure I couldn't do, but I managed to do it." And now, as a recent 40-year-old, you know, like, that happens from time to time, for sure, but not all the time, you know? It's like...

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And now occasionally, I have things where I was like, "Oh, I was sure I could do that," and then I failed, you know? And you're kind of like, oh, you can blame conditions, you can blame whatever, but you're kind of like, "Oh, I really thought I would do that, and I fell off anyway," and you're like, "Damn it."

Andrew Huberman: What is the role of aging in climbing, traditionally and how you're experiencing it? There are fields of science, like mathematics, where the stereotype is, you know, it's a young person's game, and then there are fields like biology, which is a bit more incremental, and people can have fantastic discoveries and long careers. Those are academic cerebral endeavors. But, you know, we have our understanding of this for every sport. For climbing, what's the lure for climbing and for free soloers in particular? That it's an old man's game, it's a young man's game? Woman's game, excuse me.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: I don't think anybody calls free soloing an old man's game. But, no it could be. But no, I think in general, climbing has more longevity than most sports, just because it's relatively low-impact on your body. It's very technique and, like, movement focused, and so it's not just pure physical strength. That said, I mean, climbing is in the Olympics now, and the people winning the Olympics are all sort of 18 to 23-ish, you know, sort of same as gymnastics type of range.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: So I think at the most elite levels of climbing performance, it's kind of similar to gymnastics probably. But then to do interesting, new things on real rock outdoors, I think there's a much wider latitude.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: You know, it's like-- And then even into your 50s and 60s, there are plenty of climbers who are leading expeditions to new places, developing new climbs, you know, doing things that are noteworthy and sort of meaningful for the climbing community, even though they're not necessarily cutting edge physically.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: So, I think there's a lot of opportunity for climbing, more than most sports. And I think actually, and the other big thing with climbing is that in so many other sports, like, think ball sports, you know, NBA, NFL, baseball, whatever, it's kind of like if you don't make the team, then you're done playing forever. Like, you'll literally never play football again if you're not a professional football player. Whereas with climbing, even if you're not playing at the highest level, you can still go climb all the time, and you can still do cool climbs. You can still do things that matter. You can help teach. You can do whatever. And so you can kind of, like, stay in the game much, much longer.

Andrew Huberman: You mentioned that climbing's in the Olympics now. We see a lot of sports like skateboarding and climbing now in the Olympics, and these were sports that traditionally were done... you know, people just go to where these things were done and it wasn't always recorded because there wasn't social media back then.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: More that there weren't smartphones, there weren't cameras. It's like, it's not even about the social, it's about whether or not you can record it easily.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: But-

Andrew Huberman: So, I'm guessing there's a big influx of young kids getting into this now. Do you see the sport progressing faster? And I'm also curious about the culture, whether or not... You know, any time a sport is in the Olympics, the thing is like, oh, it's kind of quote unquote "sold out now." It's going to change, it's going to become more commercial. So, what's the culture within climbing about this big expansion? What are your thoughts?

Alex Honnold: Yeah.

Alex Honnold: I mean, personally, I'm way into it. I mean, I was a kid that got into climbing in the climbing gym, and, and it's changed my life for the better, you know. Like, I love climbing, I think it's great. You know, I can certainly see the sort of commercial influx from the Olympics are sort of like more mainstream adoption of climbing. But that's kind of great, because I mean, most of my friends are sort of climbing industry adjacent professionals in some ways. You know, like, they make... They're like coaches or dieticians or setters. Like, they make the climbs that people climb on.

Alex Honnold: And so basically, the bigger the industry gets, the more people like that can make a living doing the thing that they love to do, even if they're not necessarily sponsored professionals at the highest level. So, I'm kind of like, you know, a broadening industry is kind of good for everybody. And mostly, I mean, climbing's awesome. Like, if people enjoy-- You know, it's like, why not get into climbing? It's like certainly... I mean, I think it's better than most other fitness modalities, you know. It's like, oh, why do CrossFit when you can go rock climbing? It's way cooler.

Andrew Huberman: I mean, it certainly seems-

Alex Honnold: It's way more fun. That's for sure.

Andrew Huberman: And you can do it indoors or outdoors.

Alex Honnold: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: There are probably certain aspects you wouldn't want to do alone for safety reasons, but-

Alex Honnold: I think when people ask, like, what do you worry about with climbing culture and all that kind of stuff, like with the Olympics and the mainstream appeal, I'm kind of like, you know, if somebody wants to be a climber and only go to the climbing gym in a major city for their entire life, like, that's great. If they just want to climb plastic the rest of their life, that's still better than going to CrossFit or doing whatever else. I'm like, "That's cool." Like, you don't have to go climb El Cap to be a climber. I'm kind of like, people can do whatever they want, and I think that's great for the sport.

Alex Honnold: And you are seeing standards rise very quickly right now sort of as a result. Just, like, better access to gyms, more kids getting into it. You just see talent rise faster.

Andrew Huberman: I come across social media accounts of parkour kids every once in a while doing absolutely insane stuff in urban terrains usually.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: What's the crossover, if any, between parkour and climbing of the sort that you do?

Alex Honnold: There's a little bit. Not that much, but climbers often... Competition climbing, like bouldering, which is in the Olympics, has definitely taken a slight turn towards parkour-ish sorts of moves, like big run and jumps and, crazy swings and things like that. And so some old school climbers complain that it's, like, gotten a little too jumpy, that type of bouldering. But I'm kind of into it. I mean, I don't know. This is all very, like, inside baseball. Like, how do you separate... Like, basically at the highest level, competitors are all very, very strong, so then how do you separate these different competitors who are all climbing at an elite level? And one of the ways is complicated movement like that, like run and jumps and coordination and things like that. So, I don't know. I mean, I think it's cool. I've actually met like a couple of professional parkour athletes who also climb. And they are really good at very particular sorts of things, where you're like... I mean, it's amazing to see.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, I mean, I find a lot of what they do terrifying, but also awesome. I can't help myself but watch. And, just the motivation to work it out too, like you know, because some of these are truly make or break or make or die, at least in the form they put to social media. So, I'm always curious, like, what goes into that.

Andrew Huberman: And, you know, having grown up skateboarding, I mean, you go around a city and you see stuff, and you're like, "Oh, that would be awesome." And so, I mean, just looking at a landscape, natural or urban landscape in a completely different way, I see a lot of parallels with climbing and parkour.

Alex Honnold: Totally.

Alex Honnold: Totally.

Andrew Huberman: And also, you know, I think of you at certainly at the level and kind of parallel with a guy like Tony Hawk, who's been in the sport of skateboarding for a very long time. He's an amazing ambassador for the sport as it's gone through its various, like, you know, peaks and valleys, now in the Olympics. So, I think climbing and sports like skateboarding and surfing have a lot in common in this way. Subculture, but then also gets popular.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, where they're kind of niche and then they become kind of mainstream.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: But then even once they're mainstream, they're still kind of cool, you know. Like skateboarding. It's definitely not, like, full punk rock anymore, but you're like, "It's pretty cool, you know, like, skateboarding still." And it's not that common still, you know. And that's the thing with climbing is I'm kind of like, yeah, climbing's growing, it's becoming more mainstream. It's just never going to be, you know, soccer or something. You know what I mean? It's always going to be slightly niche, slightly counter-cultural because it's just, you know, it's just a smaller thing. It's just not playing basketball or something.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, I'm intrigued by the training aspects and some of the fitness aspects. I agree that it-- Having only done it a little bit. I mean, I've been to a climbing gym once or twice.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, I was going to ask. So, you've gone to the gym and stuff.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, I've gone up and down the wall a few times.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, cool.

Andrew Huberman: I've belayed for people a few times. But I am by no means skilled at it. It'd be fun to get into because I-- Happy birthday, by the way.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Oh, thanks, man.

Andrew Huberman: I just turned 40. I'm turning 50 soon, and I think more about... I'm happy with my strength and endurance, but I think more about mobility now.

Alex Honnold: Mm.

Andrew Huberman: And also-

Alex Honnold: Climbing is great for that.

Andrew Huberman: Climbing's great for that. And there's a lot of interesting literature on brain longevity and just maintaining your cognition and the strength of your distal body. So, toes and fingers, believe it or not. It's a correlate. Like the toe strength-

Alex Honnold: Yeah, isn't that... I've always thought that's just a correlation thing. But that's not... Yeah, like, because grip strength is just a proxy for all... It means that you use your body a lot, and so therefore you're probably...

Andrew Huberman: It's just a correlation.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: You know, when I read those things about, like, if you have strong grip it means this and this and this. I'm like, "No, if you have a strong grip, it means that you do stuff all the time."

Andrew Huberman: Right.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And so, as a result of doing stuff all the time, you're probably sharper than somebody who doesn't do stuff all the time.

Andrew Huberman: That's right. So, it's a correlate. At the same time, the motor neurons that control trunk movements and contraction of the trunk muscles, like, as you go out from the midline, they're in layers in the spinal cord, so they literally, like, the motor neurons that control, like, the core sit closer to the... Sit closer in the spinal cord to the midline. And then, you know, across evolution, we evolved from animals with fins and wings, and some of the same genes are used. And eventually, you get motor neurons that control, like, fine motor movements like this.

Alex Honnold: Right?

Alex Honnold: I'm, like, sitting up straighter. I'm like, "Which ones?"

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: And it is true that for some reason, the motor neurons that control the distal body, so toes and fingers, calves and forearms, are more vulnerable to age-related degeneration than the ones for the core.

Alex Honnold: Interesting.

Andrew Huberman: So, it is possible, we don't know yet, that by maintaining strength of the distal body that you can actually preserve motor neuron and cognitive function, right? It's more of a-

Alex Honnold: Then I fricking, I'm psyched.

Andrew Huberman: Then you're set, right?

Alex Honnold: Yeah, yeah, I'm doing it.

Andrew Huberman: And that's why I was curious how climbers, provided they don't fall and kill themselves, how they age. And there's other things here too, because in some sports, like football and rugby, people are getting their head hit a lot, so they don't tend to age well. But I always thought of climbers, you know, in my time up in Yosemite, I'd see young guys like you, and then I'd see these old climbers and I was like, "Man, these guys are in incredible shape."

Alex Honnold: Yeah.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, that doesn't help.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: They're lean, they're lithe, they seem cognitively fresh. So it seems like it's a sport where people hold onto their faculties pretty well.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, I think so.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: I mean, I think, you know, it's hard to say because there just aren't that many super old climbers, and then a lot of the ones that come to mind, like sort of famous old climbers, I mean, they die the same ways that everybody dies, you know, like cancer or heart disease or whatever, but in their late 80s or whatever.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: No, I think climbing is a great way to age. I mean, I have a bunch of friends who are sort of 50s and 60s who are very fit. Actually, I mean, it comes to mind, there's this friend of mine who's a philosophy professor at UNLV, at the university, but he's incredibly jacked and I think he's 64 now. I think he just became the oldest person to climb a certain grade, like 5.14, which is like kind of an elite rock climbing grade. But I think he's maybe the oldest person to have done that now.

Alex Honnold: But, he once told me this anecdote that he was at some hotel pool, like, in middle America at some conference or something, and some kid asked if he could touch his abs because he'd never seen... He was like, "Are they real?" You know, like real, because he's like-

Andrew Huberman: Because he's only seen action figures.

Alex Honnold: Yeah. Well, yeah, he's like a 48-year-old professor who's, like, shredded and some kid in the pool is like, "Can I touch those? Is that real?" You know, like I've never seen a thing like that. And so-

Andrew Huberman: It says a lot about him and about the state of our country right now.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, exactly, middle America.

Andrew Huberman: We are in this crisis of obesity, that's very serious. It goes beyond aesthetics. Yeah, I've thought about getting into climbing. The problem I had is I tried to just raw strength it. I just tried to pull up my way.

Alex Honnold: A lot of people do that.

Andrew Huberman: And obviously that's foolish. And you gas out really fast.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, that's a very common thing for adults. I mean, especially men, especially somebody like you who's already fit, and so you try to bring the tool you already have to it, and you're like, "No, you've got to drive with your legs, you can go technique, mobility." I like to say that anybody that tries climbing should think of it as climbing a really, really steep staircase, where it's like you're still walking up the stairs and you're using the handrail for balance but you're not pulling yourself up the handrail.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And most of climbing is basically a steep staircase, you know? I mean, especially outdoors. In climbing gyms, it's a little bit different, because the wall's actually vertical. But outdoors, the wall is almost always a little bit less than vertical. So it's like basically you're on a very, very steep and technical staircase, and then you're using the handrail, like the handholds to keep you balanced on the wall. But your legs should always be driving you.

Andrew Huberman: Got it.

Andrew Huberman: I still haven't done Half Dome and-

Alex Honnold: Never? You've done Clouds Rest a bunch and not Half Dome?

Andrew Huberman: No.

Andrew Huberman: Done Clouds Rest a bunch of times, run Clouds Rest, rucked Clouds Rest, but Half Dome has those cables. Yeah, yeah, I never was organized enough to do the sign up early enough in the season.

Alex Honnold: That's weird.

Alex Honnold: No, but just do it after the permits.

Andrew Huberman: Oh-

Alex Honnold: You know the cables stay up all year. So when it's out of season, they take the uprights down, but the cables just sit there and you can do it any time. It's actually way better to do it post, like after the season, because there's no permitting, there are no people, and it's, like, super chill.

Andrew Huberman: Okay, I definitely want to do it.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, just do it, do it off season.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, because my biggest concern is not that I'm going to fall, it's that someone above me is going to fall. I mean, there are a lot of-

Alex Honnold: Way better.

Alex Honnold: Well, you're strong enough to just glance them off, you know? Just, like, shrug them aside.

Andrew Huberman: Possibly. I did hear about it-

Alex Honnold: Or ideally, stop them. Right? You know?

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, ideally stop them, but, yeah, I'd love to do it. I've been going to Yosemite since I was in my teens. I love it up there. I wouldn't say it's my second home, but it's heaven. I mean, as you know, and actually one of the reasons I'm excited to talk to you among others is that I would like more people to get into the national parks, and really enjoy them, because they're... We have so many gems in Yosemite, the High Country and Tuolumne Meadows to me is like, is heaven on earth. The-

Alex Honnold: Yeah.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Oh, Yosemite, I mean, is a crown jewel. I think it's the best national park in the country.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, people forget it's only about a four-hour drive from the Bay Area or from Los Angeles. It's pretty quick. You go through a bunch of different landscapes and then boom, suddenly you're there.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, and it's like paradise. It's incredible.

Andrew Huberman: I'm curious about things in free soloing that, as a uninformed spectator, we think, oh, you know, that's the hardest part, that's the most difficult thing. But I imagine, inside of the sport, like that there are things that are very difficult and maybe even perilous that we're not aware of, like what's some of the non-obvious aspects of free soloing, if they exist? Because I always think, okay, you know, if... I can imagine, oh, that's super tough, but that might be the easier or less tough. Usually there are these kind of hidden, I don't want to call them hidden dangers, but hidden dangers in a sport. What are some things that the observer wouldn't be aware of?

Alex Honnold: Hmm.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, I'm not sure. I'm not sure what the hidden dangers are. I would say, though, that the obvious visual dangers, like, for a non-climber just watching free soloing, I think they generally misperceive all the dangers and risks involved. You know, they just see it and they're like, "That's crazy. That's what I..." You know, and whatever they're bringing to it is probably not the actual case. Just because it's hard to visually tell what's challenging in climbing, you know? You're like, "That's a vertical wall!" But if it's, like, a nice crack going over a vertical wall, that's actually quite easy and secure climbing. But then some of the other stuff, you know, if there are really small holds, you're trusting your feet, I don't know, I mean, it's just really hard to judge that stuff visually. Like, you have to do it to experience it.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: But I think that honestly the whole perception of risk around free soloing is maybe slightly misperceived by people. So with climbing in general, like if you go climbing with a rope, like if you're traditional climbing, like if you're climbing with a rope and gear and you're going to climb Half Dome, let's say. When you start climbing from the ground, you go some distance before you put your first piece of gear in, because that's just kind of the nature of climbing, you go for a ways and then you put in some gear, you clip your rope into it, and then you're protected. And then for whatever distance you're going, you're essentially free soloing to that point. You know, like, there's always risk involved in climbing, because even if you have a rope on, depending how far you're going above your last piece of gear and, you know, what the terrain is like and whether or not the rock is good and all these other factors, you're more or less safe. And so I think people look at free soloing as this binary, like if you don't have a rope, that's dangerous. And you're kind of like, "Well, any time you're climbing there are dangers, or there could be." And you're constantly evaluating those and trying to mitigate them. And so I think that's the big misperception.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Because easy free soloing is probably-- If I'm somebody, you know, who's like an expert rock climber or whatever, I've been climbing 30 years, if I'm on an easy free solo, that's almost certainly safer than a very hard, certain types of hard climbing with a rope on. You know, and most of my scariest experiences as a climber actually have been with a rope on.

Alex Honnold: Because with a rope, you're much more willing to push yourself into unknown terrain, because you're kind of like, "Surely there'll be something good just around the corner." And so you keep going around the corner and you keep not getting into good gear, and you're like, "Holy shit, it's getting scarier and scarier" Are we allowed to curse?

Andrew Huberman: Sure, yeah, yeah.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, good. Yeah, yeah. So you know, like-

Andrew Huberman: Even at each other, if you want to curse at me. Yeah.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, perfect. But so a lot of my scariest experiences have been with a rope on, because you're kind of like, "I'm sure it'll get better. I'm sure it'll get better," and it keeps getting worse and worse. And then pretty soon, you're in some position where you're definitely going to die if you fall. But you never would have climbed into that position if you didn't have a rope on, because you're just so much more conservative when you're ropeless. And when you're ropeless, you're kind of like if something seems wrong, you just go down. You know, because you're just not going to push that far.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: I saw the movie "Meru."

Alex Honnold: Hmm.

Andrew Huberman: That was pretty intense.

Alex Honnold: I mean, that's an example of pushing really fricking far with a rope on. You know, it's like because you have a rope, you're willing to just keep pushing into the unknown. But then you wind up in a position where you're like, "This is pretty fricking extreme." You know, it's like... I mean, you saw the film. It's all totally insane.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, it is insane. And I feel like ice and snow bring a whole other dimension.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, I think that in your sport, in free soloing, like the idea from the spectator side is, you know, like, "These guys, like one fall and they're dead," right?

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: I've heard you say before that's actually not true.

Alex Honnold: I mean, yeah, it's kind of true in that-

Andrew Huberman: I mean, you don't want to fall, but-

Alex Honnold: Yeah. Like yeah, it's true that at most places, if you fall off, you're going to die. But like, when I started free soloing as a kid, not that I like started and then only did that, but on my first free solos when I was young, in the back of my mind, it would always be like, "If you slip, you'll die." You know, and the reality is that there are tons of places where your foot can slip and nothing else moves. You know, like your hands are locked on, you're holding on tight, and your foot slipped, and you're just kind of like, "Oh, my foot slipped," and then you keep climbing, and it's no big deal. I mean, there are also some places where if your foot slips, you're going to die for sure.

Alex Honnold: And the key is differentiating between those. But I think when I started, you know, it was like, "If anything happens, you'll die." And as you do it more, you're actually like, "No, I mean, a lot of things can happen and it'll be fine. You just have to make sure that the wrong thing doesn't happen at the wrong time."

Andrew Huberman: I was surprised to hear you say that, yes, free soloists die, but oftentimes they die not free soloing. They die doing other things. I'm fascinated by this, not through a morbid fascination, but for a number of reasons. So, maybe you could elaborate on that a little bit.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, there's a quote in the film "Free Solo," where a friend of mine, Tommy Caldwell, who's a very well-known climber, says something like, "All the people who were big free soloists are dead now." And it kind of implies like, you know, free soloing is dangerous and they all died soloing. But the reality is that basically none of them died soloing. Like, one or two soloists have died soloing. Though my preferred statistic is that no one has ever died doing something cutting edge. So no one has ever died pushing the envelope, like doing something extreme.

Alex Honnold: There have been a couple free soloists who have died free soloing easy terrain, like just out doing something casual, and maybe a hold breaks or maybe something happens. Like, it's impossible to know what because they die. But then the bulk of other people who are sort of known for free soloing have died either in parachuting accidents, like wingsuiting or BASE jumping, or one got swept out to sea by a rogue wave. That's kind of a freak thing. One died in a car accident. You know, just like things like, you know, it's basically just ways that people die.

Alex Honnold: So all that to say, it's not clear that free soloing is the most dangerous.

Andrew Huberman: We have a friend who unfortunately is dead now, Ken Block, who was a famous rally car driver and with our photographer here at the podcast, Mike Blabac, and film crews with DC, he developed... he was one of the founders of DC, like DC Shoes, DC Skateboarding, et cetera. Rally car. Unfortunately died in a snowmobiling accident. So something very like kind of conventional for his daily life. He lived out in Utah, and you know, obviously a huge tragedy. And then you go look at kind of people who do, quote unquote "extreme sports," for lack of a better term.

Alex Honnold: Yeah.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: And you find that it's fairly common for people who are at the peak of a field, of a sport, to die doing something else that they really enjoy. And you kind of wonder like, are they pushing themselves or is it that they're just a little too relaxed? Because as you said, rarely do free soloists die like in the most difficult aspects of the climb. So maybe it's that letting go of the mental engagement. Like, there's a change in the threshold of what they consider dangerous. So unless they need to be locked in, there's just some lack of attention to detail. This is my way of trying to save your life, basically, saying anything you're doing besides free soloing, be very, very careful, please.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Totally.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, no, I appreciate that.

Alex Honnold: Rein it in.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, we need you.

Alex Honnold: No, I mean, I also would suspect that all of the people that we're talking about are all just a little... they're just bigger risk-takers in general. They're just more willing to do things like drive quickly and, you know, do whatever. Just more willing to take risk in their life, and I suppose sooner or later those things catch up with you, or they can.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Alex Honnold: Though that said, with free soloing, two of the world's best free soloists from the previous generations are still alive. You know, older men just living their best lives, doing their thing.

Andrew Huberman: Still free soloing?

Alex Honnold: Yeah. Maybe not a super high level, maybe not pushing themselves hard, but yeah, certainly could. So, a man named Peter Croft, he's a Canadian but has lived in the US forever. He was like my childhood hero growing up, and he's an incredible solo...\'a0

Alex Honnold: Actually, there's a film with him, or a scene with him in the film, "Free Solo." He's kind of like a... They kind of frame him as a mentor figure, though honestly, he wasn't a mentor, because I was too afraid to ever even talk to him, because he was such a personal hero. But I mean, he's incredible. But he's a super nice guy.\'a0

Alex Honnold: And so, we're both sponsored by The North Face now, so we're friends. We're on the same team, and so I've hung out with him at events and things. And I was having dinner with him once, and I was kind of like, "Oh, at what point did you, kind of, end the cutting-edge free soloing?" And he was like, "Oh, actually, I did a couple of my hardest solos, in terms of grades, not necessarily the most cutting-edge, but kind of the hardest grades, within the last several years." And I was like, "Really?" And he's still just kind of doing stuff and fit, and he's psyched. And he's got to be... I don't know, I don't want to offend him, but he's got to be like mid-50s or maybe 60.

Andrew Huberman: It's awesome.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, and he's just still incredible. He's still climbing all the time. And even on his rest days, he goes down into the same climbing areas to hang out with his friends and chit-chat and like, take his dog to the cliff and stuff. So, I look at somebody like him, who's basically made an entire life of free soloing. I'm kind of like, if you do it carefully, you make good decisions, I don't think it has to be sketchy.

Andrew Huberman: How awesome is it that you're friends and coworkers with one of your childhood heroes?

Alex Honnold: Oh, it's the best. That was actually, I think, one of the best things about being a professional climber, is so many of the people that I looked up to as a kid now are friends and peers and things, and you're like, "Oh, it's so great."

Andrew Huberman: It's wild, right?

Alex Honnold: Yeah, yeah. You get to hang out with your heroes, and you're like, "Not sure I would have..."

Andrew Huberman: You never would have imagined.

Alex Honnold: Yeah. No, it's amazing.

Andrew Huberman: There's some young kid out there now, thinking the same. He's like, "I'm too afraid to go up to Alex and say hello."\'a0

Alex Honnold: They should just say hello.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah. And some day you may be working together. Right?

Alex Honnold: I don't [unintelligible] I mean, in the same way that I... Yeah, totally. I mean, in the same way that I was so afraid to ever talk to Peter when I was young, and then ultimately, now he's just another nice guy, and we're friends. We climb together. It's great.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Sort of like, yeah, anybody should just say "Hi." You know, it's like if we're at the cliff, come chat. You know, it's like we're all doing the same thing.

Andrew Huberman: I'd like to take a quick break and acknowledge our sponsor, AG1. AG1 is a vitamin mineral probiotic drink that also includes prebiotics and adaptogens. As many of you know, I've been taking AG1 for more than 13 years now. I discovered it way back in 2012, long before I ever had a podcast, and I've been drinking it every day since. For the past 13 years, AG1 has been the same original flavor. They've updated the formulation, but the flavor has always remained the same.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: And now, for the first time, AG1 is available in three new flavors: berry, citrus, and tropical. All the flavors include the highest quality ingredients in exactly the right doses, to together provide support for your gut microbiome, support for your immune health, and support for better energy and more. So, now you can find the flavor of AG1 that you like the most. While I've always loved the AG1 original flavor, especially when I mix it with water and a little bit of lemon or lime juice, that's how I've been doing it for basically 13 years, now I really enjoy the new berry flavor in particular. It tastes great, and I don't have to add any lemon or lime juice. I just mix it up with water.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: If you'd like to try AG1 and these new flavors, you can go to drinkag1.com/huberman to claim a special offer. Right now, AG1 is giving away an AG1 welcome kit that includes five free travel packs and a free bottle of vitamin D3+K2. Again, go to drinkag1.com/huberman to claim the special welcome kit of five free travel packs and a free bottle of vitamin D3+K2.

Andrew Huberman: Today's episode is also brought to us by Maui Nui Venison. Maui Nui Venison is the most nutrient-dense and delicious red meat available. It's also ethically sourced. Maui Nui hunts and harvests wild axis deer on the island of Maui. This solves the problem of managing an invasive species while also creating an extraordinary source of protein.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: As I've discussed on this podcast before, most people should aim for getting one gram of quality protein per pound of body weight each day. This allows for optimal muscle protein synthesis while also helping to reduce appetite and support proper metabolic health. Given Maui Nui's exceptional protein-to-calorie ratio, this protein target is achievable without having to eat too many calories. Their venison delivers 21 grams of protein with only 107 grams per serving, which is an ideal ratio for those of us concerned with maintaining or increasing muscle mass while supporting metabolic health.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: They have venison steaks, ground venison, and venison bone broth. I personally love all of them. In fact, I probably eat a Maui Nui venison burger pretty much every day, and if I don't do that, I eat one of their steaks, and sometimes I also consume their bone broth. And if you're on the go, they have Maui Nui venison sticks, which have 10 grams of protein per stick with just 55 calories. I eat at least one of those a day to meet my protein requirements.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Right now, Maui Nui is offering Huberman podcast listeners a limited collection of my favorite cuts and products. It's perfect for anyone looking to improve their diet with delicious, high-quality protein. Supplies are limited, so go to mauinuivenison.com/huberman to get access to this high-quality meat today. Again, that's mauinuivenison.com/huberman.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Do most climbers, as they're coming up, if they have aspirations to be great free soloists or other types of climbers, do they tend to work and do other things? Or is this like a, you're all in, it's a lifestyle, you live in a van? I mean, you can also do that after achieving some degree of financial success. We know you've done that. We can talk about that. But is it the kind of thing where you have to give up other aspects of life in order to get really good at it?

Alex Honnold: That's an interesting question. I'm not totally sure, because in some ways, it depends on what you mean by achieving success as a climber. Because if you're trying to climb the hardest grades or go to the Olympics or things like that, in some ways, you're almost better off being a university student or something, like having a structured schedule, that in some ways limits the amount that you can climb, because... I don't know enough about other sports, but I suspect this is akin to powerlifting or something, where it's like if you're trying to be really, really strong, you only need to do a little bit every couple of days, and then recover.\'a0

Alex Honnold: And so, for sort of elite physical training for climbing, you really only need, say, three or four hour sessions, four or five days a week. And then it's like, what do you do with the rest of your time? And so, you might as well have a job or... And so, a lot of my friends who write code for a living or do things like that are very, very strong climbers because of the schedule that it allows, the structure.\'a0

Alex Honnold: That said, I think if you want to be a great free soloist or a big adventure climber, you're probably better off living in a van and just doing the thing nonstop, because for that, you're not trying to have that peak muscular performance. You're trying to just learn a skill and do something all the time. And so then, hours of practice, I think, matter more in a way.

Andrew Huberman: Maybe we can talk a little bit about recovery, as long as we're talking about the number of hours that one puts in. I'm sure your recovery looks different than it used to. But what do you do to recover between sessions? Are you a big believer in sauna, cold? Or is it just basically sleep?

Alex Honnold: No, I just...

Alex Honnold: No, I push my three-year-old on the swings, you know? That's how I recover, is like I play with the kids on the swings. I mean, I try to eat relatively well. I try to sleep enough. I do all the basics for recovery. But no, I mean, I basically just survive in between.

Alex Honnold: I was actually just joking with somebody that I think, as a 24-year-old living by myself in a van, I would have crazy days of climbing, and then on a rest day, I would like binge-watch an entire season of some show while eating an entire flat of Oreos, and just never even leave the bed of my van, and then the next day go out and do a speed record on something or just be like, "Ah, I'm so psyched."

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And now, I'm definitely not doing that now, or at least... No, I haven't done that in forever, because I just don't have the time and don't have... Yeah, so I think now it takes a little more effort to recover, and it's just a little slower, probably.

Andrew Huberman: So, all this...

Alex Honnold: But it's hard to say, though, because a lot of that is just having kids and just having different demands of time and life.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: But it sounds like climbers are pretty grassroots in their training and techniques. Like, in a lot of other areas...

Alex Honnold: Yeah, I mean, I was living in a van. I was basically super low overhead, no team, no support. I'm just living in a car doing the thing nonstop for a decade. And so, that's a pretty scrappy approach. And I think that in the years since then, climbing has professionalized a little bit. And there's a little more money. There's a little more support. And there's just a higher level of competition. I think it'd be harder to achieve things doing just that now. I think you'd have to have a little more of a plan.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, I can't help but sense that hyperbaric chambers and red light and massage guns and all that are going to be making their way into the climbing culture.

Alex Honnold: Well, massage guns for sure are there.

Andrew Huberman: Okay.\'a0

Alex Honnold: Yeah, massage guns are there.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Yep.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Yep.

Alex Honnold: I try to roll out every once in a while.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Even when I was living in my van, I would stretch and roll out and do those types of things because you just kind of have to stay supple.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, how do you feel? How's your body feel?

Alex Honnold: Well, I mean, right now, I think pretty good.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: I don't know. Yeah, I live in Las Vegas. When I'm at home, I try to see this body worker in town once a week, Pat. Sweet Pat. He's the man. And so, I think of that as kind of a basic, just taking care of... It's like an oil change.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: It's like making sure the engine runs smoothly.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And I think as a result of body work like that, I haven't had any major overuse injuries in years. And so, that's pretty good for me.

Andrew Huberman: Awesome. Yeah, maybe it's just because historically it was what I knew, but I'm seeing so many parallels with skateboarding, where there was this time when no skateboarders lifted weights or did any kind of fitness.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, yeah, totally.

Andrew Huberman: Then that started to happen. Actually, Danny Way, who jumped the Great Wall of China, he was kind of the first person in skateboarding to like... He would do neck training because he had broken his neck surfing in Newport.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: And he was doing these, like where you swing the ball above your head. He was doing core work. And I remember back then thinking I'd sort of left skateboarding at that point.

Alex Honnold: Yeah, it was on the fringe. Mm-hmm. You're like, "That's weird."

Andrew Huberman: And I was thinking, skateboarders are going to really have a problem with this, because it wasn't consistent with the culture. Now, there are a lot of guys who work out and are taking care of their bodies.\'a0

Alex Honnold: Totally.

Andrew Huberman: But there are still a lot of guys who absolutely kill it. They're incredible, and their energy drink is a beer. And their quote, unquote, "nootropic" is cigarettes, and they murder it. They're super good. And so, I like these sports where it's like, you can't get around just investing a massive number of hours doing it, and then you can either take the kind of rock and roll track into it, or you can take the kind of self-care track. And sometimes people cross over, but you know, it works either way.\'a0

Alex Honnold: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: It really does.

Alex Honnold: Climbing still has that exact same thing going on, where you can kind of go either way. I do think, though, that the self-care track will obviously win out long term. I mean, that's the thing with climbing being in the Olympics and just the professionalism, all that. I mean, obviously, self-care is better for you long term.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Because, like, everybody knows that. That said, you still see a lot of very proficient climbers who, yeah, exactly, just kind of party, go hard. I mean, because so much of climbing just comes down to effort when you're doing the thing. Like, if you go climbing several days a week, and you try your absolute hardest every time you're climbing, you're going to get pretty freaking good, you know, whether you do red light therapy or any of the weird other stuff or not.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: \'a0Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: So, it's like, I mean, it really just comes down to your effort doing the thing.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And so, yeah, I mean, you could live... And I mean, a lot of climbers, especially in the past, lived on a diet of cigarettes and coffee and fricking beer. And you can get by that way.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, the 1970s-'80s approach.

Alex Honnold: It's not ideal.

Andrew Huberman: It's not ideal. A friend of mine, Tom Bilyeu, he is very successful in business. He also has a podcast, and he was saying to me the other day, he goes... Yeah, basically, when young people ask him how to get good at whatever, business or anything, he just tells them, "Work as if smartphones didn't exist." Meaning, when you're bored, go work on the thing. When you don't have anything...\'a0

Alex Honnold: Totally.

Andrew Huberman: Like, if you get rid... I'm not encouraging people get rid of their smartphone, but I'm curious about your relationship to technology because I think nowadays, even though there are people training for the Olympics and whatnot, it is very hard to disengage from pressures of sponsors, pressures of just sheer communications, right?

Alex Honnold: Totally.

Alex Honnold: Mm.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: And if you're coming up, this idea that you always have to be in contact with people, it limits the total number of reps that you get physically, but also mentally.

Alex Honnold: Totally.

Andrew Huberman: Because I imagine there was a lot of time sitting back in bed and thinking about climbing.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Just like I used to sit back in bed and think about experiments when I was in graduate school.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Now I'd probably... If that... If phones didn't exist... I'd probably be on my phone.

Alex Honnold: Now that time would be full of something.

Alex Honnold: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: I used to think about experiments and figures and what would this work, and that work. So, what are your thoughts on kind of a mental engagement separate from climbing?

Alex Honnold: No, I think that's definitely a big thing. I mean, I think... I've thought in the past that, in some ways, I feel kind of lucky that I came up when I did in climbing, where it's like sort of pre-smartphone, pre-social. You know, you just live in your car, and you do the thing, and that's it, and that's your whole lifestyle. I mean, currently, I have all the social media accounts and things, but I don't have any of the apps on my phone. I have a friend that manages it for me. I send all the content to her, but she'd post stuff. And so, it's a nice way to sort of disconnect myself from scrolling aimlessly. I don't really have the time anymore anyway. You know, it's like I'd rather play with my kids than scroll.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Sure.

Alex Honnold: But no, I mean, that's tough. I mean, I think it'd be hard to be a kid now growing up, like thinking that that's the norm, that you have to be connected, that you have to be capturing everything, documenting it, and then sharing it and posting it, and just all the stuff. I've always felt like the thing about being a professional climber is that you just have to be a good climber. Like, first and foremost, the key to being a professional climber is being able to climb really well. And the most important thing is doing the thing. And I just think when you get caught up in all the posting, sharing, streaming, all the whatever, that's not doing the thing, you know? But it's easy to conflate them, and it's... I don't know. Yeah. No, I think it'd be really hard.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, I agree completely. And the hidden secret is that if you want something interesting to show on social media, the key is to not be on social media so you have something to bring to it.

Alex Honnold: Totally.\'a0

Alex Honnold: It's just so hard to actually be good at something, and it's...\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: And this goes back to what we were just talking about with free soloing and perceived risk and all that kind of stuff, is, it is really easy to make something look rad, soloing-wise.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.\'a0

Alex Honnold: Like, I could climb the outside of this building, and it would look insane. It would get tons of likes. People would think it's cool. But it's not cutting edge. It's not cool. It's not even hard. Like, it's not... It's whatever. But to actually do something that's cutting edge or newsworthy in climbing is pretty freaking hard.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: You know? And the challenge with social and with public, all that kind of stuff, is that it's just so easy to... I don't want to say to fake it, because it's not like people are out there trying to be duplicitous or to trick you. But it's just you can get the same splash with none of the effort through social stuff, I think. You're like, "Oh, I just did something easy, and people thought it was amazing. Let's call that good." And you're like, "Well, that's just not good because it's easy." It's freaking... You know, it's not cutting edge. It's not rad.

Andrew Huberman: I mean, you clearly go after big, big goals. I mean, it's a giant goal. I think it really stands... And I know you've been told this many times before, so, if it embarrasses you in a positive way, then great. I mean, it stands as perhaps at least one of the most impressive physical feats in history, because the risk consequence scenario there was, you fall, you can potentially die. There may have been moments along the climb where...

Alex Honnold: Few brief moments, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, brief moments.

Alex Honnold: Where you're right above a ledge. You're like, "Oh, wow."

Andrew Huberman: Right. Yeah. So, okay, and it's so like you to point out those moments as opposed to all the other moments. It really speaks to your mindset. But I think that going after big things, I mean, building rockets to go to the moon. I remember when I was a kid, Danny Way decided to jump the Great Wall of China, to do it live. Someone had died trying it on a mountain bike. I remember thinking... I watched it on a little screen this big, and it was like I've known that guy since... We're out of touch now, for the most part, but since I was 13, and he was always going after big things, jumping out of helicopters, jumping the Great Wall of China, you know.\'a0

Andrew Huberman: And then there are people who just push themselves. And so, what I wonder is, on a daily basis, when you climb, do you ever just climb for fun? When you climb, are you always working on something? And there's this famous scene in "Free Solo," more or less immediately after you got down from the climb, you're fingerboarding again, and you're training, and you're enjoying your routine, which, by the way, is consistent with keeping the dopamine flowing for process as opposed to the postpartum depression that many people experience after a big feat is completed. Selling a big company, et cetera.\'a0

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: You avoid all that by doing exactly what you're doing. But then how quickly did your mind pivot to like, "Okay, what's next?" In the domain of climbing, because I realize you've had two children.

Alex Honnold: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: You've got other aspects of your life. But where's your mind in terms of where you want to take your life and your climbing?

Alex Honnold: Yeah. On the one hand, I set big goals, I guess, something like El Cap. But the thing is, I would actually say that's more the outgrowth of setting consistent little goals like all the time. I basically always have a running to-do list of, "What am I doing tomorrow? What am I doing today? What am I trying to do this week?" And that extends to climbing as well, with what are all the little things I can be doing? What are the little things I can tick this week?\'a0

Alex Honnold: You know, I have my climbing journal that goes back to 2005 or 2006 or something. So, basically, everything I've ever climbed is logged with difficulty and times and whatever. And so, I'm constantly trying to tick things as a climber, just like to do new climbs that I haven't done before. And so, I mean, I think actually, my day of climbing yesterday could be a good example of this. So, yesterday, my wife and I dropped off our older daughter at school, went to the cliff, did a day of sport climbing, and then picked up our daughter on the way home. It's like a perfect day like that, where you can kind of make it all work.\'a0

Alex Honnold: And I'm not going to be able to go to that cliff very often this season just because of travel and work, and life, basically. So, I don't want to have any big project there, because I just won't have time to do it. You know, I'm trying to set my goals appropriately, where I'm like, "Oh, there's no point in trying to do something that would take me a month or two to achieve if I only have three days."\'a0

Alex Honnold: And so, I had a goal for that day of trying to do this very particular little combination of routes that I hadn't done before. It's just something new, something interesting. It's not that hard. But then we got there, and it was like the worst condition. It was like 86 degrees when we parked the car. And so, it's like you're trying to work out in horrendously hot.

Alex Honnold: And it was also that kind of monsoony, so it was very humid. So, we got to the wall, and it's disgusting. And I was kind of like, "Well, you know, it's a training day." Like, whatever. And so, I tried to do this new combination of routes. Ultimately I failed on it. I fell at the very freaking top of the wall. I was so maxxed and didn't do it. I'll probably get a chance to go back on Monday and I'll for sure do it then.\'a0

Alex Honnold: But you know, it's like a very small goal. Like, this isn't cutting edge, like big. This isn't even cool at all. Like, my friends won't even care. Like, they'll think it's stupid. But it's nice for me to have a reason to try my hardest for that particular day of climbing. And I think that the big goals come as a result of all those little things. Like, if day-by-day, you're constantly doing something that's a little bit new, a little bit different, a little bit harder, you know, whatever seems like the appropriate challenge for that day, I think that looking back at 20 years of climbing outside non-stop, that the big things have just come as a natural outgrowth of all those little things. You do enough little things all the time, and then every once in a while, something big happens.

Alex Honnold: And so, I don't know. You know, but I have to-do lists going back years of like goals and all these aspirations. And some years, I only do half of them. Some years, I do a third of them. And then, something like free soloing El Cap sat on a list like that literally for years, and it kept floating to the next year, to the next year. Because you get into Yosemite, and you look at the wall, and you're like, "No, that's not..." You're like, "It's totally out of the question." And so, you just punt to the next year. And so, yeah, I mean, sometimes the goals don't happen, sometimes they do. But you kind of just have to let it play out. It's more like the day-to-day little challenges.

Andrew Huberman: I love how matter-of-fact you are about it. You are wired different.

Alex Honnold: You think? I mean...