How to Expand Your Consciousness | Dr. Christof Koch

Listen or watch on your favorite platforms

My guest is Dr. Christof Koch, PhD, a pioneering researcher on the topic of consciousness, an investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science and the chief scientist at the Tiny Blue Dot Foundation. We discuss the neuroscience of consciousness—how it arises in our brain, how it shapes our identity and how we can modify and expand it. Dr. Koch explains how we all experience life through a unique “perception box,” which holds our beliefs, our memories and thus our biases about reality. We discuss how human consciousness is changed by meditation, non-sleep deep rest, psychedelics, dreams and virtual reality. We also discuss neuroplasticity (rewiring the brain), flow states and the ever-changing but also persistent aspect of the “collective consciousness” of humanity.

Articles

- A framework for consciousness (Nature Neuroscience)

- Cortico-thalamo-cortical interactions modulate electrically evoked EEG responses in mice (eLife)

- Cognitive Motor Dissociation in Disorders of Consciousness (The New England Journal of Medicine)

- Recovery Potential in Patients Who Died After Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment: A TRACK-TBI Propensity Score Analysis (Journal of Neurotrauma)

- A survey on self-assessed well-being in a cohort of chronic locked-in syndrome patients: happy majority, miserable minority (BMJ Open)

- The will to persevere induced by electrical stimulation of the human cingulate gyrus (Neuron)

- What is it like to be a bat? (The Philosophical Review)

- Complex slow waves in the human brain under 5-MeO-DMT (Cell Reports)

- Exploring 5-MeO-DMT as a pharmacological model for deconstructed consciousness (Neuroscience of Consciousness)

- Randomized trial of ketamine masked by surgical anesthesia in patients with depression (Nature Mental Health)

- Invariant visual representation by single neurons in the human brain (Nature)

Books

- Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life

- Letters

- The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life

- Meditations

Other Resources

- Joseph Emerson (pilot) case

- Non-sleep deep rest (NSDR)

- The Twelve Steps (Alcoholics Anonymous)

- Perception Box

- #thedress

- Terry Schiavo

- A Tribute to Oliver Sacks from Colleague and Friend Christof Koch

- Charlie Kirk assassination

- Intrinsic Powers, Inc

- Spiegel im Spiegel (Arvo Pärt)

- The End of Children (New Yorker)

- Single gene variant is what keeps small dogs small (Science)

Huberman Lab Episodes Mentioned

People Mentioned

- René Descartes: French mathematician, philosopher

- Plato: Greek philosopher

- William James: American psychologist, philosopher

- Elizabeth R. Koch: American publisher, writer

- Thomas Bayes: English theologian and mathematician

- Oliver Sacks: British neurologist, author

- Francis Crick: English molecular biologist, Nobel laurate

- Jeremy Bailenson: professor of communication, Stanford University

- Josef Parvizi: professor of neurology and neurological sciences, Stanford University

- Steven Pinker: Canadian psychologist, author

- Immanuel Kant: German philosopher

- Aldous Huxley: English writer, philosopher

- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: French priest, philosopher

- Daniel Dennett: American philosopher

- Arthur Schopenhauer: German philosopher

About this Guest

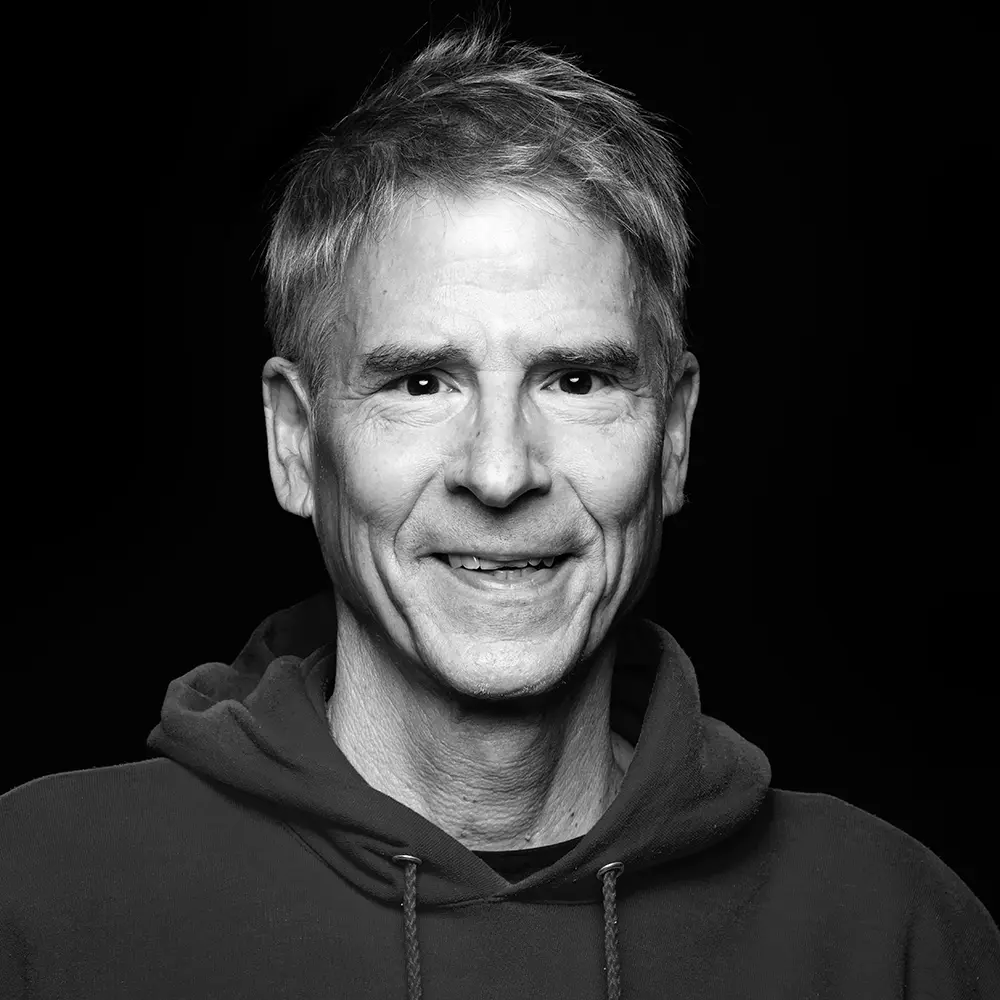

Dr. Christof Koch

Christof Koch, PhD, is a pioneering neuroscientist, investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science, and the chief scientist at the Tiny Blue Dot Foundation.

This transcript is currently under human review and may contain errors. The fully reviewed version will be posted as soon as it is available.

Andrew Huberman: Welcome to the Huberman Lab podcast, where we discuss science and science-based tools for everyday life.

Andrew Huberman: I'm Andrew Huberman, and I'm a professor of neurobiology and ophthalmology at Stanford School of Medicine.

Andrew Huberman: My guest today is Dr. Christof Koch. Dr. Christof Koch is a neuroscientist and investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science and the chief scientist at the Tiny Blue Dot Foundation. He is considered one of the great pioneers and luminaries of modern neuroscience. Christof's research has spanned how we perceive the world around us, how different states of mind arise and shape our experience of life, and, most notably, consciousness. I joined the field of neuroscience way back in the 1990s, and even way back then, Christof's name and his work were considered seminal for our understanding of the brain and human experience. And over the subsequent 30 years, he has continued to do incredible, groundbreaking work.

Andrew Huberman: Today, we discuss consciousness, what it is, literally, at the level of quantifiable brain mechanisms, and how understanding consciousness at that level can help you experience life more richly and allow you to place deeper meaning on everything from a typical morning to grief and loss to your greatest and most awe-inspiring moments. Christof also explains how our individual experiences and memories place us each into a unique, what he calls, 'perception box,' which is what shapes your outlook on life, and in many cases, your quality of life, including your mental and physical health. And he explains how you can change your perception box through what we call neuroplasticity, which is the modification of brain circuits.

Andrew Huberman: We also discuss what flow states, psychedelics such as DMT and other psychedelics, meditation, sleep, and dreaming tell you about how your mind works and the nature of consciousness. And we don't just discuss consciousness at the level of individuals. We discuss the collective consciousness of humankind. So, if you're somebody that's interested in the brain and mind, what it means to be human, how to evolve and improve your mind, today's discussion will address all of that. Oh, and we also discuss dogs, cats, Jennifer Aniston, and the meaning of life.

Andrew Huberman: So get ready. This is a very special episode of the Huberman Lab podcast that I'm certain, by the time it finishes, will have you thinking differently about your life, and dare I say, with a bit more optimism.

Andrew Huberman: Before we begin, I'd like to emphasize that this podcast is separate from my teaching and research roles at Stanford. It is, however, part of my desire and effort to bring zero cost to consumer information about science and science-related tools to the general public. In keeping with that theme, today's episode does include sponsors. And now for my discussion with Dr. Christof Koch.

Andrew Huberman: Dr. Christof Koch, welcome.

Christof Koch: Thank you for having me, Andrew. It's been a pleasure. It's been more than a decade, 12 years since we last interacted.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, I've always enjoyed our interactions, and one of the reasons is that you're always into something super interesting, big, big questions and evolving fast all the time, all at once. So, I think most people have heard the word consciousness. They perhaps have pondered consciousness, but at least to my mind, it's not a very well-defined word. So when you talk about wanting to understand consciousness, or about having consciousness or being in a moment of consciousness versus say, a rock, which I'm presuming doesn't have consciousness, what are we talking about? And here we could be using biological language, psychological language, or philosophical language. Please include all of it because-

Christof Koch: Much simpler.

Andrew Huberman: Okay.

Christof Koch: Do you hear me?

Andrew Huberman: Hmm?

Christof Koch: Do you hear me?

Andrew Huberman: Yes.

Christof Koch: Do you see me?

Andrew Huberman: Yes.

Christof Koch: The fact that you hear, not that you respond to my sound by moving your hand. The fact that you see, not the fact that you can navigate around this room, but you actually have a picture in your head.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: The fact that you love, the fact that you hate, the fact that you dream, that you imagine, that you dread. Those are all conscious experiences. It's the stuff of life, literally. If I give you a billion dollars, okay, that even for you is probably a meaningful amount of money, but let's say-

Andrew Huberman: Well, it certainly is, yeah.

Christof Koch: Okay, but there's a slight, you know, thing that I'm going to remove all your conscious experiences, so you would still love and hate and drive cars and do everything else you do right now, but there would be no light. There wouldn't be any Andrew. Would you take that wager?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hm..

Andrew Huberman: No.

Christof Koch: Well, the difference between those two states is consciousness. So without it, you don't exist for yourself. In fact, tonight you're going to go to bed, in particular in the early stages of the night, you go into non-REM delta wave sleep, right, and you do not exist for yourself. If I wake you up, I said, "Andrew, Andrew, something's happening," and I ask you, "Well, where did you come from?" You say, "I came from nowhere," which is different, of course, later stage in the night, right, when you have a dream, which is another conscious experience, but when you sleep, you do not exist for yourself. When you're under anesthesia, you do not exist for yourself. So you only exist for yourself because you are a conscious being. So in some sense, it's very simple to define.

Andrew Huberman: Historically, has it been defined as a simple just presence of self and perception of the outside world, the way you're describing it? I feel like consciousness has been twisted and turned, and, you know, weaved into balloon animal form over so many hundreds of years that people tend to argue about consciousness. And then they start getting into discussions about free will versus no free will, but why, given the simplicity and the clarity of your explanation, have people struggled with this definition of consciousness so much?

Christof Koch: The study of consciousness is really a modern phenomenon. It's really René Descartes. So, you know, Aristotle and Plato, much as they are the foundational fathers of philosophy, they didn't really have a position on the mind or on consciousness. That's a modern thing. Where we have struggled is trying to put it in objective form. So, you don't access my consciousness, and I don't access your consciousness. And this makes it different from anything else that we study, different from a black hole, from a virus, from a brain. Because all those I can study with what philosophers call 'third-person properties,' right? You can stick them in a magnet. You can point a telescope at it. We can agree on what's the wavelength, what's the weight, what's the mass, what's the molecular constituency.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: We can't do that with consciousness. I believe you're conscious. In fact, I ask you, "How are you feeling today?" You tell me, "Well, I'm a little bit depressed because of what happened." Well, so I'm trying to get at your state of consciousness, but ultimately it's always an inference, whether it's you, or whether it's a baby, or whether it's an animal that can't directly talk because language is another way to infer. So that makes it more difficult, and the other part is that people confound consciousness with consciousness of self. So most people, if you ask them, "What's consciousness?" they say, "Oh, it's to know that I'm a man and I will die one day and I know what I had for breakfast." Those are all conscious experiences, but they really pertain to self-consciousness.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: But that's just one aspect. You can lose self-consciousness... Like, I know you had Alex Honnold here, and I know from reading and listening to some of what he says, he says when you're really climbing at an expert level, you flow over the rock.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: You're sort of high, you totally lose a sense of self, that inner voice, that critic that constantly speaks to you is gone during those moments.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: There's this blessed silence, but you're highly conscious because you're highly conscious of where you are and what's the next place you need to go to. And of course, during psychedelic experience, during states of flow, during states of meditation, you can lose yourself, but you're still conscious. So let's not confound self-consciousness, which is one aspect, a big aspect, particularly in adult people, literally highly educated people, with consciousness that took over. That's really a much broader set of... The fact that you can feel your limbs, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: That may not even relate to you, just feel something there without assigning it, "Well, that's my body." That is, again, it's another conscious experience.

Andrew Huberman: The liminal states between sleep and awake, in both directions, falling asleep and waking up... Do you think they offer any windows into this deeper understanding of consciousness, or does one even need a deeper understanding of consciousness? For instance, I'm a big fan of yoga nidra, which I've described as non-sleep deep rest. You deliberately lie down, do long exhale breathing to slow your heart rate down, bring down your levels of autonomic activation, more parasympathetic, et cetera. And the idea is you stay awake while deeply relaxing your body, a very atypical waking state that is more similar to rapid eye movement sleep, when the brain is very active, the body is paralyzed, as you know.

Christof Koch: Lucid dreaming?

Andrew Huberman: It's a state of mind where... The instruction in the classic yoga nidra scripts, and this goes back thousands of years, is to move your mind from thinking and doing to being and feeling. You're supposed to be in pure sensation. This is the idea. And as one does that, 10, 20, 30 minutes, and you do it repeatedly over your life, as many days as you do. I've been doing it since 2017. I can feel my-

Christof Koch: You do this every day?

Andrew Huberman: Every day for 30 minutes. Yeah. I can feel myself falling asleep, but not quite falling asleep. So it's a little bit like lucid dreaming, but then as you remind yourself to bring your perception to your body surface or your heartbeat, your breathing, whatever it is, and stop making plans, you lose past and future, and you become hyper-present. But something about your sensation and perception merges with thinking, and it's like you-

Christof Koch: But Andrew, is Andrew still there?

Andrew Huberman: Yes, I'm definitely still there. I'm definitely still there. You're not out of the body.

Christof Koch: But you don't mind-wander in the past or in the future?

Andrew Huberman: No. No, and it becomes very easy to do this, so you actually feel as if you're falling a little bit. Like the vestibular system probably shuts off a little bit as you're going into this, and you feel as if you're falling into it. And the classic definition, and I've tried to translate this to physiology, but they talk about once you eliminate thinking and doing, and you are more in a being/feeling state, what they called 'the energy body,' is more accessible. It's almost like you're feeling things within your body, and it's looping back on itself. Now, this all sounds very mystical, but what we're really talking about is more interoception, feeling, you know, you're moving your perceptual awareness, as you know, to things from skin inward. It's a very unusual state, but yes, I'm still there in yoga nidra. I'm not someplace else. I'm actually more in my body than in any other state.

Christof Koch: Well, you could also be simply not there at all.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Where Andrew isn't there, the self, the one that carries your traits and your personality, your memories, but you're still conscious.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: That's interesting because it is very relaxing to emerge from this. It's a great tool for replenishing physical and mental energy, and I've tracked sleep while in this, and there are some really nice brain imaging studies now of people doing yoga nidra, also called 'non-sleep deep rest,' and pockets of the brain go into regional sleep as opposed to what we normally see during sleep.

Christof Koch: Anon-

Christof Koch: Whole brain.

Andrew Huberman: So it's an interesting state. I'll send you a script to maybe give it a try and see if it means anything to you.

Christof Koch: I would be... I'm interested in all these different states of consciousness because it's all...

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Christof Koch: I mean, it's dominated by everyday waking consciousness. But as you said, that's all about doing, right? You walk, you run, you shop, you look around, you talk to people, but there are all these other states that don't involve the William James time streams of consciousness, but they are all conscious experiences.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: And so, the more we know about them and the physiological basis, the better we can describe and delimit what consciousness is and what it is not. So, for instance, to your point, consciousness is not primarily doing. Of course, we can do things, right? We do it all the time. That's how we make a living. But consciousness is really more about being. It's a state of being. And by the way, that's also why computers, they can do everything we can do, but they can't be what we are... Conscious.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: But that's-

Andrew Huberman: Please elaborate on that.

Christof Koch: We confound consciousness and behavior because we talk. We're speaking apes, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: But if you take that away, you are still highly conscious. If you don't move, if you meditate or sleep or you have a mystical experience, you're sitting... Or a psychedelic experience, you're sitting or lying, you're not moving any body, hardly any overt movement, yet you're highly conscious, right? So, behavior is not required for consciousness, and consciousness, of course, is not required for behavior. There are all sorts of unconscious behaviors. And so, we shouldn't confound the two. And this relates in an interesting way to the confounding between intelligence and consciousness when people talk about artificial consciousness and artificial intelligence. Intelligence ultimately is about planning to do something, about behavior in the short term or in the long term, while consciousness is a state of being. Being happy, being sad, being full of dread, or seeing something which is really different.

Andrew Huberman: I'd like to take a quick break and thank one of our sponsors, BetterHelp. BetterHelp offers professional therapy with a licensed therapist carried out entirely online. I've been doing weekly therapy for well over 30 years, and I've found it to be a very important component to my overall health.

Andrew Huberman: There are essentially three things that great therapy provides. First of all, great therapy provides good rapport with somebody that you can really trust and discuss any issues with. Second of all, it can provide support in the form of emotional guidance or directed guidance toward specific actions you want to take in your life. And third, expert therapy can provide you with useful insights, insights that can allow you to make changes to improve your life, not just at the emotional level, but also your relationship life, your professional life, and on and on.

Andrew Huberman: With BetterHelp, they make it very easy to find an expert therapist that can help provide these benefits that come through expert therapy, and it's carried out entirely online, so it's extremely convenient. No driving to the therapist's office, no looking for parking, et cetera. If you'd like to try BetterHelp, you can go to betterhelp.com/huberman to get 10% off your first month. Again, that's betterhelp.com/huberman.

Andrew Huberman: Today's episode is also brought to us by Our Place. Our Place makes my favorite pots, pans, and other cookware. Surprisingly, toxic compounds such as PFAS or forever chemicals are still found in 80% of nonstick pans as well as utensils, appliances, and countless other kitchen products. As I've discussed before in this podcast, these PFAS or forever chemicals like Teflon have been linked to major health issues such as hormone disruption, gut microbiome disruption, fertility issues, and many other health problems, so it's really important to try and avoid them.

Andrew Huberman: This is why I'm a huge fan of Our Place. Our Place products are made with the highest quality materials and are all completely PFAS and toxin-free. I especially love their Titanium Always Pan Pro. It's the first nonstick pan made with zero chemicals and zero coating. Instead, it uses pure titanium. This means it has no harmful forever chemicals and does not degrade or lose its nonstick effect over time. It's also beautiful to look at. I cook eggs in my Titanium Always Pan Pro almost every morning. The design allows for the eggs to cook perfectly without sticking to the pan. I also cook burgers and steaks in it, and it puts a really nice sear on the meat. But again, nothing sticks to it, so it's really easy to clean, and it's even dishwasher-safe. I love it, and I basically use it constantly.

Andrew Huberman: Our Place now has a full line of Titanium Pro cookware that uses its first-of-its-kind Titanium nonstick technology. So if you're looking for non-toxic, long-lasting pots and pans, go to fromourplace.com/huberman and use the code HUBERMAN at checkout. With 100-day risk-free trial, free shipping, and free returns, you can experience this terrific cookware with zero risk.

Andrew Huberman: I'm curious about the stability of self-representation. As you know, there are many conditions related to brain lesions, strokes, injuries, et cetera where people will lose their memories of the past, or the inability to form new memories emerges. But one of the things that seems so rigid is one's notion of self. Like a baby coming into the world very quickly learns that they have a name, they have a self, that self interacts with other things, and I'm not aware of any clinical conditions where people lose themselves completely for long periods of time.

Christof Koch: Derealization.

Andrew Huberman: Derealization.

Christof Koch: Well, derealization is one where you feel... So, A, you're perfectly right. The self is the basic kernel of our operating system.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Okay? And it's very difficult for us to lose because if we lose it, we would not be, from an evolutionary point of view, in a good shape, right? But then there are conditions where you feel... So, for instance, in derealization, a psychiatric condition, which can, by the way, happen during psychedelics, you feel not you anymore, and you feel there's something off with the world. This is not the real world. There's something funny. The world... They still see and hear fine, but they all believe that this isn't the real world, and they try to wake up. In fact, you probably remember a year and a half ago, there was a spectacular case of the Alaska Airlines pilot who asked to go onto the jump seat on a flight from Everett in Washington to, I think, Oregon or San Francisco.

Andrew Huberman: I've flown that from Everett. Tiny airport.

Christof Koch: Yes.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Christof Koch: And then they said, "Of course." He's a colleague. He was a pilot in good standing. Into the flight, he stood up and tried to pull the two switches that would kill the fuel to the two engines. The pilots fought him and kicked him out of the cabin, and he was arrested. In fact, the trial was three days ago. What happened was that for the first time ever, he took psychedelics three days earlier at a wake for his best friend, and then he went into this episode of derealization where he thought, "Okay, this is not the real world. This is a dream. I need to wake up. And if in my dream, if I crash the plane, then I will finally wake up in the real world."

Andrew Huberman: Whoa.

Christof Koch: So, yes, it is very robust but of course... So I call it, we always live in the gravitational field of planet ego. It is always about me. It is always about me, me, me. And even if I don't think explicitly, there are things that are, you know, there are processes monitoring my consciousness to make sure that it's always important for me.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: And it's very rare, but of course, the self can also be highly dysfunctional, right? You can catastrophize, you can be highly anxious, you can think people are insulting you, or they say bad things about you, while in fact they don't at all. And so there are rare conditions of selflessness when, just like an astronaut that can become weightless, you can become selfless.

Andrew Huberman: Hmm. Interesting.

Christof Koch: So during episodes when you are experiencing a state of flow... I used to have this when I wrote computer code, when I was way younger. You can totally get absorbed by it, right? Or you read a book, or you read an engaging movie, or you play some sports or something, or you're Alex Honnold and climb, right? And partly these states are so addictive because it's such... You've just realized you spent the last 20 minutes in this heavenly state doing something, but again, the critic is gone. And of course, during high, sometimes heroic doses of psychedelics, you can also totally lose yourself, the sense of self, and you realize how profound, beautiful the world is without you. You know, the self being there and constantly interfering and relating it to, "What does it mean for me?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: What does this give me?"

Andrew Huberman: It's incredible. We're definitely going to talk about psychedelics, and I've experienced some of this loss of self in psychedelics before. I'm also interested in more subtle shifts in self that are nonetheless still profound. Perhaps the most dramatic shift in self I've ever experienced that was pervasive after the kind of incident, was I have a colleague at Stanford, Jeremy Bailenson, he's a real pioneer in the VR space. Very early on, he started using VR, and there's an experience you can have in his laboratory if you go there, which is you put on the VR goggles... He had a big room for VR with padded walls so no one runs into the walls, and it's called, I think, 'Walk of 1,000 Cuts.'

Andrew Huberman: It's very interesting. So, obviously, I'm white, you're white, so I don't know what it is to experience racism. I've never actually experienced racism just by virtue of when I grew up, where I grew up, and I'm white, and I'm living in the United States. I'm sure there would be those that would argue that there are white people who have experienced racism, I haven't, and I certainly hadn't at the time of this VR experience. So in this experience, you put on the VR glasses, and if you're white, you look into a mirror in the VR, and you see your face slowly contort to somebody who's black. Okay? And it's still you, but you're black. And then you go into the world in the VR space, and you go to a job interview, and you walk down the street, and it's very interesting.

Andrew Huberman: Now, the stimuli are designed to evoke a certain response. But as you walk down the street, for instance, you notice that white people look at you in a certain glance. And they actually control pupil size in these other subjects very well, very carefully. And then you go to the job interview, and there's this experience where at the end of the job interview, there's someone else there, and they shake the hand of the other person, who is also not white but isn't black. And so, there's a number of subtle experiences, and then you catch onto what's happening, right?

Andrew Huberman: You go, okay, these are these little not-so-micro experiences that have an emotional load. You come out of that VR experience. It's very interesting. And then you go back into life, back on campus, and go and do it. You never forget it. It's so interesting, like, never have I forgotten the experience. So when you walk down the street, now I notice when people don't glance my way, if they glance my way, how they glance. And so, I can't say what it is to be black. I've only ever lived in this body.

Andrew Huberman: I can't say what it is to be anything except myself, but in a very brief, maybe 10-minute VR experience, completely transformed my understanding of what it is to be a different self, which I think is pretty interesting. I don't think I've ever had a movie experience, or a play, or hearing a song that had quite as profound a shift internally, so clearly there was plasticity there. I just would love your thoughts on the self as a modifiable entity, not just losing self, but like, how much can we actually change who we are at the level of perception and consciousness?

Christof Koch: So I would call it the transformative experience.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Right? We all know changing behavior is very difficult, but there you're telling me within 10 minutes, because of this 10 or 15 minute VR experience, you're now much more hyper-aware of this. So that's a rare experience, and I think it would be useful for all of us to have those.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: So I work with somebody here in Santa Monica, Elizabeth R. Koch... We're not related, although we share the last name, and she has this really interesting idea of what she calls 'perception box,' that we all run around with our own view of reality. You'll see how this relates, including, most importantly, my notion of self. And it's not objective, it's all subjective. It's just like a Bayesian thing, you know, the modern language would be Bayesian priors. I have various Bayesian priors of how I expect myself to be, and how I expect other people to respond to me.

Andrew Huberman: Do you want to explain Bayesian for people just briefly?

Christof Koch: Okay. So Bayesian is a view of uncertainty in the world that was sort of... There's this famous British vicar, Thomas Bayes, in the 17th century who started this, so this is called Bayesian, whereby I look at something and I try to infer, well, what's the underlying reason for it, and I update my... Based on certain observations that I make, I continuously have this running estimate of what I think is really going on, and this also includes my base assumption about the world, including political assumptions, including assumptions of how people will react, or what's the true motive of people.

Christof Koch: So the point that she's trying to make with this perception box, it includes everything. So a benign, funny example is, do you remember what we call '#TheDress'?

Andrew Huberman: Oh, yeah.

Christof Koch: Okay? So remember, this was the dress that went viral in 2015, where it was a wedding dress, where if you looked at it, half of the... Roughly, I can't remember the exact percentages, but half the people saw it unambiguously as gold and white. That's how I see it. There's no question.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. Same. Yeah.

Christof Koch: Okay, same. But half of the other people see it as blue and black. And again, they don't... It's not something, guessing is it maybe one or the other? They just see it blue and black, or... Okay, so then people ask, "Well, is there anything real? What is the real color?" Often, people get asked. No, there is no real color.

Christof Koch: What there is are photons from the sun that strike the two-dimensional surface of the dress that get absorbed by my photoreceptors, that then get processed, and they get evaluated in one way in our brain, so we see it as white and gold, and get valued differently in a different brain because we all have different priors. This has to do with whether we are evening persons or morning persons.

Christof Koch: But this also applies to things like 9/11 and October 7th. If I tell you this, 9/11, what do you think about it? Or October 7th, depending on whether you are an Israeli or a Palestinian, you have profoundly different views of it, right?

Christof Koch: So you look at a fact that's supposedly objective, but depending on what priors you bring to it, what your perception box construct is, in what culture you grew up, you have radically different interpretation, and this also includes your sense of self. So I would say what you had was this transformative experience. You expanded your perception box, that your perception of reality to now includes the notion, "Huh, I get it now that other people, depending on their skin of their colors, will be treated differently from me."

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: That's invaluable. And I wish we all had that.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, and I got to experience a sliver of what the emotional experience is like because it was an emotional response in Andrew, right? And in many ways, it was far more informative than any documentary I've ever seen or any movie, which had a profound effect on me while I watched them, but didn't change the way that I think about how I interact with others on a moment-to-moment basis. Because I don't consider myself racist, and I didn't then. And you notice in this VR experience the way that the... I have a friend who's a psychologist who says, "You know, the subtle informs the gross." The way these little things change the way that you feel, and then the way that you interact, and then it starts to feed back on what the expectations of you are, whether or not you live into or combat those expectations. And what I realized is it's a hell of a lot of work. There's like a burden of mental load that was not familiar to me before. And the-

Christof Koch: Implicit and explicit.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Yeah, so you have to think about it.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Christof Koch: What does it mean? What does it mean for my behavior? What does it mean for other people's behavior? Yeah, so you can call it... In psychedelics, this is called the integration period.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Christof Koch: So I would submit you had a transformative experience.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: You had what philosophers call 'direct acquaintance,' now with some form of racism, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Subtle racism, right, in this VR, and now you're doing the explicit work of reformulating everything.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: You're changing, literally, your Bayesian priors.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: So I imagine you're top-down, you know, from, let's say, prefrontal cortex back into whatever theory of mind, for instance, areas, right? You are changing your priors.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: It was really striking given how short the experience was, and how first-person it was, right? Obviously, with VR, it's not like watching a movie. You are the movie. You're in the movie. You're the first-person actor in the movie.

Christof Koch: So I think there are two ways to achieve a transformative effect. One is the slow one, by educating yourself, by reading books, by watching movies. But as you said, very often it doesn't really bite until you have a direct experience. You directly have acquaintance with this.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Then suddenly you say, "Now I get it." And this is the character of any transformative experiences, including mystical experiences.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Recently, I was at Esalen, this beautiful place on the Big Sur coast that-

Christof Koch: Yeah.

Christof Koch: I mean, it's just up here, right? Around 200 miles or 300 miles up the coast.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, although they've shut it down. The freeway fell out some years ago south of Esalen, so you have to go up and around now from Southern California, where we are now.

Christof Koch: Oh.

Andrew Huberman: Still an incredible place that's been very seminal in the mindfulness movement, and just a gorgeous place to visit for many reasons. But while I was there, I had an incredible experience that involved you, although you didn't realize it, and it wasn't a psychedelic experience, nor was it a dream. I went into the bookstore, and I found a book of one of my favorite humans that I unfortunately never met, which is Dr. Oliver Sacks, who's now deceased, right? Great neurologist, writer. And it's a book of all his letters, and there are a couple of letters in there to you.

Christof Koch: Oh, that's how it is.

Andrew Huberman: And I have a very close relationship with all things Oliver Sacks. I'm a collector of many of his things. So, one of the most interesting things about him and one of the things that he wrote to you about in this book, I don't know if you've seen this book, is he describes his efforts to understand consciousness and the human brain better by literally taking some time, presumably without psychedelics, and imagine what it is to be a bat, to be...

Christof Koch: I have.

Andrew Huberman: We know bats aren't completely blind, but to essentially navigate and sense the world without vision as the dominant sense, to experience through sonar, and he would spend time thinking about being a bat up in the corner of the room, or a cephalopod like an octopus, or a cat. And, you know, you read this and you go, "Okay, this guy's crazy," right? "This guy must be crazy." But I realize now, based on everything you've said so far, that he was very far from crazy. He was hyper-sane in this regard, because as difficult as it is to lose oneself, and to go into the mind of another human, the VR experience that I had clearly demonstrates to me that it's possible, and yet we have a very hard time imagining what it is like to be non-human.

Andrew Huberman: And nowadays, with the emergence of AI and fear about, you know, merging of humans and machines, I think it's going to be ever more important that we understand what kind of flexibility we have in moving from human consciousness to non-human consciousness. So, I would love your thoughts or any stories you have about Oliver. I simply adore him through the writings I've consumed. But I think this practice of pretending or trying to shift one's consciousness to that of another animal is just profound, and I like to think it also can bring us closer to the animals that we curate as pets. Dogs in particular. So, I'd love your thoughts about this, or Oliver, or all of the above.

Christof Koch: Yeah, he was a great friend. I visited him many times. I met him through Francis Crick, and we had this shared interest in the brain and in consciousness, and he was incredible. I mean, what made him so singular, also in his interaction with patients, was his empathy. So he could have deep empathy with patients and try to imagine himself, you know, these strange otherworldly conditions, right? Like the patient from Mars, or these other patients that he described who had very specific pathologies that were totally explainable as arising out of brain lesions. Yeah, he was better at that than most other people. Trying to imagine what is it, for example, to live in the eternal present, right? He had one patient who had this profound amnesia, but he could still... He always lived back in the... I can't remember now.

Christof Koch: 20 years earlier, and his entire world, his entire memory stopped 20 years earlier, and that's how he lived. And it looks crazy, but once you understand that, it makes perfect sense how he responded. So we each have a bespoke reality, right? So you have slightly different receptors, you may have different color receptors, you may have different taste receptors. You have a certainly different experience from me, right? You grew up in a different environment. So, it's not easy to get into someone else's head, although some people can do it. Actors, for example, can try to do it, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: The method acting, right? Where you totally try to adopt the point of view of the character you're trying to play. But of course, that's much more difficult for other animals that share or we may share a close evolutionary history, like with all mammals, but that have very different... You know, that may have infrared sensors, or they have a much more potent sense of smell, and how do we... That have a different motor system, that hangs from the ceiling, right?

Christof Koch: So how do we imagine doing that? But I think it is possible. It's challenging of... And of course, it's this classical essay by Thomas Nagel, "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?" right? And his position, this American philosopher says, "Well, we can never truly know what it is like to be a bat, but I think we can approximate it." I can't really ever know what is it like to be Andrew Huberman, right? But I can try to imagine it. And you know, this is what empathy is, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Trying to feel like you, and trying to realize that we're all conscious beings, we all are bookended between two eternities. And so, in some sense, we're very, very similar, and the thing that divide us are really tiny subsets of all the things that we share, including with cats and dogs and elephants and squids, and everything else on the tree of life.

Andrew Huberman: Before we talk about your experience with DMT and psychedelics more generally, I wonder to what extent, you know, changing our consciousness is possible in a very directed way. So, what I'm referring to here is, for instance, a lot of therapies, whether or not it's a cognitive behavioral therapy, or it's MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD, or whether or not it's just really trying to get more REM sleep each night so that you can unload the emotional weight of previous day experiences, which seems to be a hallmark of REM sleep... Many people accumulate experiences that they feel either define them or burden them; this is very common, in fact, and they would like to live the remaining portion of their life, however long, without the emotional load.

Andrew Huberman: They don't necessarily want to forget the experience, but they want to remove the emotional load. And it seems like, in pathogens like MDMA, in proper clinical settings, can help do that. That proper cognitive behavioral therapy can help people really talk through and work through, maybe have a cathartic experience, but unload the emotional component of the experience. So what I'm referring to here are things bad. But it could be positive things like the day that your child was born, or something where you're trying to update your conscious experience of life going forward and in the present by way of very deliberate tailoring of your memories. Do you think this is possible?

Christof Koch: Of course, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Christof Koch: And you just gave me an example. Your experience of VR and realizing what it is to have a Black skin compared to a white skin, right? This was clearly a beneficial experience that enables you to be more emphatic with other people, right? And try to better understand what they mean when they talk about 'explicit' or 'implicit' racism, right? And it changed you profoundly, and you're telling me this happened when? 2000 and...

Andrew Huberman: This was probably 2017.

Christof Koch: All right. So, you know, that's eight years ago, right?

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: So clearly, it lasted.

Christof Koch: So, I think for most conditions, we can certainly improve them. You have to believe that you can change, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: So if you're being told all the stories, "It's all the system. There's nothing you can do. It's just hopeless. You can just, you know, take this pill and suffer through to the end of your days."

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: That, I think, is highly counterproductive. No, you have to believe, "I'm an active agent of my own mind. I can shape my reality," I would call it my perception box, with various ways, either talk therapy or psychedelic therapy, or some other therapy.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: It requires a lot of work. It doesn't come sort of for free, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: At the end of the day, I'm still left, let's say, with my traumatic memory, but now I can realize, 'Okay, I had this bad experience, but it doesn't have to define me. I can go on past it.' And there are various ways we can talk about that this can be achieved. Absolutely. I do believe in the malleability of the human mind, even in older people. In almost every condition, you can, but maybe except for the most extreme, you can change your outlook on life if you really want to. That's one issue, right?

Christof Koch: It's a little bit of trying to convince somebody who's an alcoholic that they should stop drinking until they have the realization, "Okay, I don't want to land in the gutter anymore. I don't wanna wake up at, you know, 8:00 AM in the morning, drunk outside my house. I wanna change." Then you can change. And, you know, 2,000 years of therapies, of all sorts of things... Take Alcoholics Anonymous, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: The first thing you do, you have to recognize that, "I am an alcoholic."

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: And then I can begin... Before I do that, there isn't really a hope, but once I do that, I can change. It may be difficult, it may be arduous, but you can change.

Andrew Huberman: We've known for a long time that there are things that we can do to improve our sleep, and that includes things that we can take, things like magnesium threonate, theanine, chamomile extract, and glycine, along with lesser-known things like saffron and valerian root. These are all clinically supported ingredients that can help you fall asleep, stay asleep, and wake up feeling more refreshed. I'm excited to share that our longtime sponsor AG1 just created a new product called AGZ, a nightly drink designed to help you get better sleep and have you wake up feeling super refreshed. Over the past few years, I've worked with the team at AG1 to help create this new AGZ formula. It has the best sleep-supporting compounds in exactly the right ratios in one easy-to-drink mix. This removes all the complexity of trying to forge the vast landscape of supplements focused on sleep, and figuring out the right dosages and which ones to take for you. AGZ is, to my knowledge, the most comprehensive sleep supplement on the market.

Andrew Huberman: I take it 30 to 60 minutes before sleep, it's delicious by the way, and it dramatically increases both the quality and the depth of my sleep. I know that both from my subjective experience of my sleep and because I track my sleep. I'm excited for everyone to try this new AGZ formulation and to enjoy the benefits of better sleep. AGZ is available in chocolate, chocolate mint, and mixed berry flavors, and as I mentioned before, they're all extremely delicious. My favorite of the three has to be, I think, chocolate mint, but I really like them all. If you'd like to try AGZ, go to drinkagz.com/huberman to get a special offer. Again, that's drinkagz.com/huberman.

Andrew Huberman: Today's episode is also brought to us by Helix Sleep. Helix Sleep makes mattresses and pillows that are customized to your unique sleep needs. Now, I've spoken many times before on this and other podcasts about the fact that getting a great night's sleep is the foundation of mental health, physical health, and performance. Now, the mattress you sleep on makes a huge difference in the quality of sleep that you get each night.

Andrew Huberman: How soft it is or how firm it is all play into your comfort, and need to be tailored to your unique sleep needs. If you go to the Helix website, you can take a brief two-minute quiz, and it will ask you questions such as, "Do you sleep on your back, your side, or your stomach? Do you tend to run hot or cold during the night?" Things of that sort. Maybe you know the answers to those questions, maybe you don't. Either way, Helix will match you to the ideal mattress for you.

Andrew Huberman: For me, that turned out to be the Dusk mattress. I started sleeping on a Dusk mattress about three and a half years ago, and it's been far and away the best sleep that I've ever had. If you'd like to try Helix Sleep, you can go to helixsleep.com/huberman, take that two-minute sleep quiz, and Helix will match you to a mattress that's customized to you. Right now, Helix is giving up to 27% off all mattress orders. Again, that's helixsleep.com/huberman to get up to 27% off.

Andrew Huberman: It's interesting that you bring up 12-step and AA in particular because the next step, besides acknowledging the problem, at least in AA, is to acknowledge an inability to solve it oneself, and a giving over of some of the process of eliminating alcohol to another, what they refer to as 'higher power.' Some people call this 'God,' some people call it 'Jesus,' some people, you know...

Andrew Huberman: But it's more or less a requirement of AA that you agree that you can't do it alone, and you can't do it just with other humans, but you need other humans. They're necessary, but not sufficient. The recognition of the problem, other humans, and community are necessary but not sufficient, but this kind of externalization, like you need help from outside the self, that's not from humans. Very interesting.

Andrew Huberman: They don't say, "You need to go get a dog." They don't say, "You need to commune with nature." They say, "You need to embrace a higher power." It's very interesting given the effectiveness of AA. It's one of the most successful ways for people to continually avoid alcohol.

Christof Koch: It's true. I acknowledge that. I personally wouldn't say it requires divine intervention because I'm not sure there is such a divine entity that could intervene in this. But acknowledging and also acknowledging that it's, "I can't do it by myself. I would say at least I would need community. I would need help from others." Again, you have to acknowledge that.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Well, maybe it's the opening up of space that-

Christof Koch: The willingness. The willingness.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah. And maybe it's, "I couldn't do it by myself until now." And in order for there to be a different future visualized, maybe there is a sort of creating of space. I mean, this is actually probably a good opportunity for us to talk a little bit about the neurobiology underlying consciousness, and then we'll get back to plasticity.

Andrew Huberman: You know, we're both neuroscientists. And for many years, '80s and '90s and even prior, the emphasis was on brain areas. Amygdala, fear. Hippocampus, memory. Prefrontal cortex, decision-making. This kind of thing. And of course, there's been this beautiful transition to a focus more on circuitry, areas and networks, activated more or less over time. Can we look to particular networks or network phenomena, circuit activation patterns, and say, "That's the origin of consciousness"? Or is that no longer a meaningful pursuit?

Christof Koch: Yes.

Andrew Huberman: Why did I have a feeling you were going to answer that way? Yeah.

Christof Koch: So, A, there are certain enabling conditions, okay? One enabling condition, your heart has to beat because if your heart doesn't beat, it doesn't supply oxygen to your brain, and you will "lose consciousness" within eight to 10 seconds, okay? Same thing in the brainstem. Your brainstem has to be active to perfuse the rest of the forebrain with noradrenaline and dopamine, all of that. But those don't provide the content. You don't love or you hate or see with your brainstem, with your locus coeruleus, for instance, okay?

Christof Koch: So the circuits that convey experience in us, I'm not saying it's the same in other species, particularly non-mammals, but in us that grew up with a normal brain. Again, I'm not talking about people who never... You know, anencephalic individuals. That's very different.

Christof Koch: So, for most of us, we grew up with a normal brain, and I think the relevant circuits are the corticothalamic circuits. And in fact, we can exploit this knowledge now to test whether someone is conscious, because in principle... So, what you can do, you can knock the brain using a technique called 'transcranial magnetic stimulation,' right? And then you listen to its echo using a high-density EEG net, okay? And you can see if you knock here or here, depending on where exactly you knock, you get these up and down states. And if they last for, let's say, 200, 300, 400 milliseconds, and they occur at different places, you can formally compute what's called 'brain complexity' using Lempel-Ziv complexity.

Christof Koch: And you can show when everyone who's either awake like us, or we're asleep in a dream state, or we're on ketamine, where we're dissociated... In all those cases, the brain complexity's high. It's above a threshold. However, when you're in a non-REM sleep, when you're in a state of deep sleep, or you're anesthetized, or, of course, in the most extreme case, you're brain dead, then the brain complexity is very low.

Christof Koch: And in animals, we've even done at the Allen Institute, this experiment where we can systematically manipulate the corticothalamic cortical circuits to show that it is this circuit that is really the one that's critically involved in consciousness. In fact, so what we discovered over the last 10 years, there's this very abrupt threshold in brain complexity defined using this technique where... So, there's a thing called 'Perturbational Complexity Index.'

Christof Koch: It's a single number, PCI between zero and one. Zero means there's no complexity. It's flat like in a dead brain, flat line. One means every electrode is totally independent from anyone else. Never happens in a real brain. In a real brain, typically a wake brain, you get things between 0.65 and 0.8, let's say. There's a sharp threshold at 0.31. Anyone that we've had... No, no, there are 300 people, both patients and normal people, that have been measured... If you're above the threshold of 0.31, you're conscious. If you're below this threshold, you're unconscious.

Andrew Huberman: Hmm.

Christof Koch: That probably means there's this non-linear... Just like Hodgkin-Huxley, there's probably a non-linear circuit mechanism that, once the circuit is intact, it's sufficient to support consciousness.

Christof Koch: Now you can ask, "Well, this is all very nice. Why is this relevant?" Well, it is relevant in the following case, something that could happen to any of us. I step out here onto the Pacific Coast Highway. I get hit by a car, okay? I'm now unconscious. I get to the ICU, whether that's a traumatic brain injury, or cardiac arrest, or hemorrhage. I'm unconscious. I'm like this... I might be aroused, so you know, my eyes are open. I'm now what used to be called 'vegetative state,' what's now more often called 'behavioral unresponsive state.' Okay? And there are thousands of these people worldwide, because with proper care, with proper nursing care, you can stay in this state for weeks or months, or in the case of Terri Schiavo, 14 years. Okay?

Christof Koch: Furthermore what happens, typically, in most cases, after four to five days, the doctors will talk with their loved ones, "Is this what he would have wanted?"

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: And 70% to 90% of the time, they decide no, this is not what you wanted, and you withdraw life-sustaining therapy. But we now know that 25% of these patients have what's called 'covert consciousness.' They're there. We know this because, for example, some of these patients you can... There was a big study last year in the "New England Journal of Medicine," made a front page of "The New York Times," where you can show that 25% of these patients can still voluntarily up and down regulate their motor cortex in response to a command. Clench your fist for 30 seconds, relax it, clench your fist for 30 seconds, relax it. So these people that, otherwise, when you ask them, "Sir, can you hear me? Can you track my finger?"

Christof Koch: Can you pinch them very hard to see do they do a withdraw of limb reflex, they don't do any of that. So they have what's called a Glasgow Coma Scale, or a very low GSCR Scale, but they still seem to be conscious. They either have high brain complexity, or they can modulate their brain. So, this is now the first time ever that we have a practical way in people that cannot respond, that clinically, behaviorally are considered unresponsive, first to convince the family that although their loved one doesn't respond, doesn't mean that they're unconscious, and then try to see, "Well, okay, so this person is conscious, can we now give particular treatments to enable them to recover?"

Christof Koch: We also have some pilot data to show that those patients that are conscious, compared to the patient that are truly unconscious in this behavioral wakefulness state, that they have a better chance of recovery.

Andrew Huberman: Incredible. This 0.31 you said is the threshold? On the one hand, it seems so reductionist. On the other hand, it makes total sense, right? I mean, you need enough coherent brain activity to be aware of self, be aware of what's going on around you, and respond to it. Below that, like in falling asleep or being asleep, you don't have that except in dreams, of course. And it sounds like a wonderful clinical tool, because this is obviously many people's worst fear, that somebody's in there, you take them off life support, and they would have emerged. You mentioned Terri Schiavo was the last...

Christof Koch: Schiavo.

Andrew Huberman: Schiavo.

Christof Koch: Terri Schiavo.

Andrew Huberman: Can you just remind people what the outcome of that situation was?

Christof Koch: Yeah, so this was a case back in 1998 or 2000 under President Bush. She had a cardiac arrest, where the heart was started up again. She was in this state for 14 years. And then there was this fight between her husband, who said that she didn't want to be in this state, and her parents, that were profoundly devout that said, "No, we want to keep her alive."

Andrew Huberman: I see.

Christof Koch: And went back and forth, and finally, the court allowed her a withdrawal of life support. So she died after 14 years.

Andrew Huberman: I see.

Christof Koch: And the analysis, the postmortem showed in her case, her brain was totally shrunk. So in her case, you know, if we didn't do this procedure, then we didn't have it, but clearly, she was probably one of the 75% of patients that are truly unconscious.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Yeah, so it's important to get this into the ICU. So, in fact, I started a company called Intrinsic Powers because it's the intrinsic powers of the brain that mediate consciousness, and we're now trying...

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: We met with the FDA, and they said, "Well, this is all cool, but you really need to do a clinical trial." So we're trying to fundraise now, so if anyone in the audience here is willing to invest in this, to get this procedure into the ICU so we can tell for sure, is this patient conscious, or they're just non-responsive? Because those... So, it pertains to what we said early on. The fact that you don't behave is not the same as the fact that you're unconscious. Those are two different things.

Andrew Huberman: Very, very interesting, and very important work. Has there ever been an example in the reverse direction where somebody was in one of these, what used to be called 'vegetative states,' right, and then emerged after, say, a period of six months or a year, and is living perfectly normally in the world saying, "Thank you so much for not taking me off life support?"

Christof Koch: Yes. So, A, typically people don't... When they do recover, they typically don't have explicit memory, because again, memory is something different than actually being, you know, conscious experience, just like most of us don't remember our dreams.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: We're clearly conscious, but we don't remember them.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: But they are there. There's a study now systematically at Harvard that tries to explore that, and some people explicitly say that. In fact, there's one really interesting case where the person who then recovered, a young guy. First, he was upset that they didn't follow his explicit instruction to terminate life, but then, of course, later on, now he's relatively normal, he was very happy that they saved him.

Christof Koch: Yeah, so we can pull back, you know, particularly with modern technology, 9/11, et cetera, rescue helicopters, we can pull back people from the brink of death, but that may not be the same as having them actually conscious. So, the medical community is now beginning to recognize this idea of covert consciousness, which is something that was only really realized over the last 10 years.

Andrew Huberman: Amazing. Well, I turn 50 in two weeks, and I'm working on my will, something I never thought I would do, but here I am doing it. So I'm going to include a section on this 0.31 threshold, but also maybe perhaps, pending new technologies.

Christof Koch: Medical directive.

Christof Koch: Yes, that's the trouble because-

Andrew Huberman: Right, you don't know what'll be available in a few years.

Christof Koch: You don't know... yes.

Andrew Huberman: Right.

Christof Koch: And the other thing is called this 'disability bias.' So, let's say... You look like a person who's highly active, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: So you probably cannot imagine being in a state where you can't move anymore.

Andrew Huberman: I mean, I've thought about it, but not in a real way. I mean, I fear it. I wouldn't want that. I love being able to move and see, among other things, those are probably two of the most important things, movement and vision, right?

Christof Koch: Oh, okay. But now you have to change your prior. You've had this accident or whatever, now you are in this state. This is a given.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: You're now in the state where you had a bad, whatever, car accident, and you can't move anymore, or you may not be able to see. Now, what is it you want? And to those people that you can communicate with... Like, they did a study in Israel with a locked-in patient, right? So these are patients that have a stroke at the level of the pons, where there are typically most of their motor commands they can't execute anymore, except, you know, some neck and some vertical eye movements.

Christof Koch: And they ask them, because they can communicate. And most of them, except the ones that have chronic pain, most of them want to continue to live. Although before, when you would have asked him, he would have said, "No. No way." And so, it's difficult with this medical directive because you don't know until you get there.

Andrew Huberman: Well, I like the answer you just gave, because it speaks to the durability of the human spirit.

Christof Koch: Yes, the resilience. Yes.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, the desire to keep going is pretty spectacular.

Christof Koch: Yes.

Christof Koch: Yes.

Andrew Huberman: And there are amazing examples. Like I was introduced some years ago to somebody from the Special Operations community who, unfortunately, stepped on an IED and lost use of his legs. But he's a phenomenal surfer. Like, he literally drags him-

Christof Koch: Wow.

Andrew Huberman: And he won't let people carry his stuff down the cliffs. Like he drags himself down to the waves, and he gets down there, and he can get up on... He has prosthetics that he can use, but for partial movement on land. But he basically is on his torso, and he's an athlete.

Christof Koch: Whoa.

Andrew Huberman: He's a Paralympic athlete, and serious athlete, and super driven. And when you first interact with him, you see the pictures of before and after, and this kind of thing, you go, "Oh gosh, that would be so..." But he's living in the moment. I mean, I'm sure he has his struggles, surely, but he's living in the moment of what's possible, and at least in his words, "The desire to persist and to continue to pursue goals is fundamental to not getting lost in the what could have been." He really exists... Of course, he was a former Navy SEAL, et cetera, so it's probably part and parcel with the psychology that got him there. But he exists in the what's possible, not what's impossible landscape most of the time, it seems. It's pretty spectacular.

Christof Koch: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: The human will to continue to live.

Christof Koch: The resilience.

Andrew Huberman: I'm very struck by this brain area, the anterior mid-cingulate cortex. I don't know if you're familiar with it.

Christof Koch: Yes, I am.

Andrew Huberman: But, right, Joe Parvizi's laboratory.

Christof Koch: Yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Stimulating it, people feel as if there's a challenge confronting them, and they're going to lean into it. We've talked a lot about this on this podcast as a key site for plasticity of all things. And the friction that's required, but also this element of the will to live, because it turns out the anterior mid-cingulate cortex is larger or more active in people that are the so-called 'SuperAgers' that maintain cognition. So-

Christof Koch: Well, there's also this phenomenon of akinetic mutism that's also found in lesions, that area where people seem to have completely lost their will to do anything at all. They just sit there all day, and they don't say anything. They've lost essentially their will to do or say anything. And if you inject them with dopamine or others, then sometimes they retrieve, and you ask him, "Why was it?" "I just had no desire."

Andrew Huberman: And do we know what brain area is involved in this case?

Christof Koch: Yeah. It's the cingulate.

Andrew Huberman: Uh-huh.

Christof Koch: It's part of the anterior cingulate.

Andrew Huberman: Okay. So maybe it's the same structure. I mean, the human will to live and to continue to evolve oneself, I mean-

Christof Koch: May also have a physical substrate.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah. I believe it does. I mean, I think cingulate cortex seems to be a key hub.

Christof Koch: Well, and so based on the study of your colleague Josef Parvizi, right, at Stanford, so we know that if you go a little bit back into the posterior cingulate, that's where you have the sense of self. If you stimulate there or in these people who have epileptic seizures in there, right, they have these weird dissociative states, or where they feel themselves floating, or they can hear themselves have a conversation, but observing themself having a conversation.

Christof Koch: So we know some of the sense of self here. And we also know that doing meditation and doing psilocybin, those areas are reduced. So yeah, there is a footprint for everything we experience. There is a footprint in the brain. That doesn't mean we can reduce it to the brain. Not at all. But there is a physical neuronal correlate of it. And Francis Crick and I, of course, used to call this the 'neural correlates of consciousness,' and tried to pursue it.

Andrew Huberman: I'd like to go back into the perception box, because I'm really intrigued by this.

Christof Koch: Well, you never left the perception box, because it is your construction of reality.

Andrew Huberman: Oh, okay. Well-

Andrew Huberman: I, uh... People are getting a sense of how your brain works, and I love it. It's been a while since I've seen you, as I forgot how much fun it was. Inside the context of the perception box, I'd like to explore something that's very relevant today. It's 9/11. Yesterday, Charlie Kirk was killed, assassinated at a discussion on a campus. And there's a mix of responses to this out there. Some people are greatly saddened, others less so. There's a lot of discussion about morality, about words versus actions. Maybe we use this as a bit of a filter to understand something.

Andrew Huberman: Broadly speaking, I can imagine two somewhat extreme ways to go through life. One is with the philosophy, you know, "live and let live." As long as somebody is not hurting somebody, let them do what they want. They want to change genders, let them change genders. They want to vote Republican, let them vote Republican. They want to... You know, as long as they're not harming anybody, right?

Andrew Huberman: So we have laws to protect people's well-being. The other extreme would be one of kind of moral judgment. Like, you know, people offended by someone else's choices or even beliefs. And even if they can't point to the exact harm that's being done, they feel as if it's grating on them, right? And then, of course, we have a lot of questions about those two different people's histories, whether or not they see, you know, moral judgment in the context of who's getting more or less resources. There's a bunch of evolutionary stuff we could weave in there. But let's just examine like two perception boxes, one of a "live and let live" type... And I'm not trying to politicize this at all. It could be right wing, left wing, middle, whatever. It doesn't matter.

Andrew Huberman: Let's be aliens in outer space... A live and let live-dominated perception box versus a moral judgment perception box. Given the reality of these perception boxes here on Earth now, how is it that one can possibly establish a species cohabitating Earth that's going to go forward in any kind of different way without something fundamentally changing about, A, understanding that there are these perception boxes, B, how to change them? And then, as you said before, there has to be a desire to change them.

Andrew Huberman: So, I mean, it feels a little bit like a stalemate, in fact. And I'm not trying to be pessimistic. I think I'm being realistic. As long as you have people are live and let live and others who are in a state of moral judgment, I just don't know how 100 years from now things are going to look that much different. There'll be different conflicts.

Christof Koch: Oh, they could be worse, of course.

Andrew Huberman: Could be worse, could be worse.

Christof Koch: Could be far worse.

Andrew Huberman: But I can't imagine, like, unless we let dog consciousness play a key role or something-

Christof Koch: Well, we could also have what some people in the Bayesian community call a 'meta-prior.' So you have your priors, right? So, the priors are all the assumptions that let you judge, supposedly, a fact. So, to stay with yesterday's examples, trying not to politicize it, but you may have read, after the assassination was announced in the House of Representatives, the speaker called for 30 seconds of silence, which was fine. And then someone called for prayers out loud, and then all pandemonium broke out. Okay? So among the representatives, they screamed at each other. You know, it only took this one thing and then suddenly... Because they have radically different priors, they just have... They're partly, you know, your two... The ones that you described.

Christof Koch: But what they should do is sort of have a meta-prior, "Okay, wait a minute. We're now screaming at each other. We all believe that shooting other people," that's what they all said, universally, "This is bad. This is not good. No matter who did it, for what reason, this is bad and evil." "Maybe we should stop screaming at each other to change our higher order prior, because this isn't going to end well if... This just keeps on getting worse. And where is it gonna end? How is it gonna end?" There has to be this insight. So it's a little bit when we talked before about Alcoholics Anonymous. There has to be this inside weight. "We can't do this." There has to be a realization that there is a problem, and we've got to do things differently.

Andrew Huberman: Well, I think for many, many years, the meta-prior was God and religion. People looked to texts that were, at least, people agreed, scripted by non-human actors, so the meta-priors.

Christof Koch: Human actors.

Andrew Huberman: Maybe now people will look more to AI, I don't know. But I just feel like humans are not well-positioned to resolve certain kinds of things for ourselves and-

Christof Koch: Yeah. We have lost the common...

Christof Koch: If we lost this narrative, yeah.

Andrew Huberman: Yeah.

Christof Koch: So we had more or less... I mean, in the '50s and '60s, right, there were three TV channels, and we had a common narrative. I totally agree with you.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: And we lost that. And we're never going to regain that, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: Unless there's extreme political repression, you know, maybe in China, but not here. It's not going to happen here, right? So what do we do? Is this just getting worse every day with more and more violence and other things? Or is there going to be some point an awakening, a meta... You know, a realization that we've got to change our priors here?

Andrew Huberman: What do you think is the potential role for AI? I mean, is... AI, you said machines, you know, they don't do, right? They... Or they only do, they only do.

Christof Koch: They do.

Andrew Huberman: Excuse me. They only do. Like with AA, first comes the acknowledgement that humans are not sufficient to resolve these issues on our own. I'm not saying where the answer should come from. I have my own ideas about that, but it seems like there needs to be the acknowledgement that we are limited in our ability to resolve this. History demonstrates that, yesterday demonstrates that, today demonstrates that. I mean, it's naive of anybody who's been alive for more than a few decades to think that in 30 years, suddenly everybody's going to, you know, put down swords for plowshares, right?

Christof Koch: Okay, but humanity has bumbled through history for the last, you know, however long, several million years.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: And modern history, since we can speak and have recorded thought, at least 10,000 years, right? So, ultimately, somehow we'll make it through, most likely.

Andrew Huberman: On the whole.

Christof Koch: On the whole.

Andrew Huberman: But it could be much better, right?

Christof Koch: Individuals, empires crumble in half. And of course, we're an empire like any other empire.

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: And yes, this Western-style liberal democracy, you know, you can be pessimistic about it. And, you know, it's not just the US. Of course, here it's the most because we have all these guns. But if you look at, you know... You look at in Hungary, look at in Germany, look at in France, right? They now have these countrywide protests against everything.

Andrew Huberman: Against everything?

Christof Koch: Yeah. And then, of course, England, right? And so, yeah, so we're certainly... The Western ideal, Western national state's liberalism is certainly in a crisis. What's going to help? And adding AI, of course, just accelerates everything, right? We're going through this acceleranda, this tremendous acceleranda, right? Where AI is getting better literally every day, right? I'm sure you use it just as much as I do. It's very powerful. It's getting ever more powerful. You throw that into the mix. Well, that's probably... With unemployment, massive change, right? Most people don't like change, right? So...

Andrew Huberman: Well, yeah, I guess what I'm trying to get to here is, you're a really smart guy. You understand consciousness. The perception box, to me, is a wonderful framework for people to understand differences of opinion and outlook that are based on history and perception, et cetera.

Christof Koch: But if it's all intellectual, it's like what you said when you've really experienced what it is to have Black skin... I mean, not fully, but to experience something of what is it like to walk around being Black, right?

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Christof Koch: You had to... You told me yourself, right, early on that you said, "Well, you can't get that from reading. You really have to experience it." So people have to have this moment, this come-to-Jesus moment where they say, "Okay, s***, we can't go on like this anymore, that we have to change our way of doing this."

Andrew Huberman: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Huberman: I agree.

Christof Koch: And with social media, you know, all it takes is a small fraction of people that reignite this, right? That post something nasty and then someone else posts it and then they all pile on and...

Andrew Huberman: Yeah, we have a billion plus channels of information.

Christof Koch: Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes.